- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

Three Weeks With My Brother Page 17

Three Weeks With My Brother Read online

Page 17

My mom tried to come up with ways to cheer me up. At least, that’s what she called it. “Paint the living room,” she’d say, “it’ll cheer you up.” Or, “Sand the door so we can stain it a different color. It’ll boost your spirits.”

Had her ideas worked, I would have been the most cheerful kid on the planet. As it was, however, I simply moped around in paint-splattered clothes, working all day on various projects, and mumbling that all I wanted to do was run and wondering why God wouldn’t help or listen to me. By mid-June, my mother had grown exasperated with my attitude, and, as I was lamenting my plight for the hundredth time at the kitchen table, finally shook her head.

“Your problem is that you’re bored. You need to find something to do.”

“I don’t want to do anything but run.”

“What if you can’t?”

“What do you mean?”

“What if your injury never gets better? Or, even if it does, what if you can’t train the way you want to anymore for fear of hurting it again? You don’t want to spend your life doing nothing.”

“Mom . . .”

“Hey, I’m just offering up the obvious here. I know it wouldn’t be fair, but no one ever said that life was fair.”

I lowered my head to the table.

“Oh no,” she said firmly, “you’re not going to just sit here at the table and keep acting this way. Don’t just pout. Do something about it.”

“Like what?”

“It’s your life.”

I raised my head in frustration. “Mom . . .”

“I don’t know,” she said with a shrug. Then she looked at me and said the words that would eventually change my life. “Write a book.”

Until that moment, I’d never considered writing. Granted, I read all the time, but actually sitting down and coming up with a story on my own? The very notion was ridiculous. I knew nothing about the craft, I had no burning desire to see my words in print. I’d never taken a class in creative writing, had never written for the yearbook or school newspaper, nor did I suspect I had some sort of hidden talent when it came to composing prose. Yet, despite all those things, the notion was somehow appealing, and I found myself answering, “Okay.”

The next morning, I sat down at my dad’s typewriter, rolled in the first sheet of paper, and began to write. I chose horror as a genre and conjured up a character who caused accidental death wherever he went. Six weeks and nearly three hundred pages later, after writing six or seven hours a day, I’d finished. To this day, I can remember typing the final sentence, and I don’t know that I’d ever felt a higher sense of accomplishment with anything I’d done in my life.

The only problem was the book. It was terrible and I knew it. It was atrocious in every sense of the word, but in the end, what did it matter? I didn’t intend for it to be published; I’d written it to see if I could. Even then, I knew there was a big difference between starting a novel and actually finishing one. Even more surprising, I found that I’d actually enjoyed the process.

I was nineteen years old and had become an accidental author. It’s funny the way things happen in life.

Because I was away from home eight months a year, my brother and I had little time to see each other. Micah continued to spend weekends trying new and exciting things. Meanwhile, my injury continued to plague me; I ran neither cross-country nor track, but concentrated on making a comeback.

I’d made good friends with a few other freshman the year before, some of whom were on the track team, and they became the ones I would depend on to get me through yet another challenging year. But I’d learned something by heading off to college. My dependence on family had diminished more than it had for either my brother or sister. Dana still lived at home and was a freshman in college; though Micah was living in his own apartment, he still made it home three or four times a week. Whenever I called home, it always seemed as if he was there.

Soon after I’d left for my sophomore year, my mom mentioned that Brandy wasn’t doing well. She was twelve years old—not old for some breeds, but ancient for a Doberman—and I could hear the concern in my mom’s voice. My mom loved her, as we all did, and when I pressed my mom, her answers were slightly evasive.

“Well, she’s lost a little weight, and her arthritis seems to be getting worse.”

When I came home for fall break, I was shocked by Brandy’s appearance. I hadn’t seen her in two months but in those two months she’d gone from being relatively healthy to a walking skeleton. Her stomach caved in, and it was possible to count her ribs from across the room. As she slowly wandered toward me, I could see the happy recognition in her eyes. Her tail—bone thin and nearly hairless—waved a slow greeting. I crouched down and stroked her softly, feeling her shake and tremble beneath my hand. I swallowed the lump in my throat.

I spent most of the next two days with the dog, sitting beside her and patting her gently. I knew even then that she wouldn’t last until Christmas; I murmured quietly to her, reminding her of all the adventures we’d had together growing up.

The day before I was to head back to Notre Dame, we woke to find that Brandy had died.

My brother and I held back our tears as we went to get our sister. Dana made no pretense of being tough, and began to sob immediately. It was the sound of her wailing that made my brother and me both begin to cry as well, and later that morning, with tears stinging our eyes, we dug a hole in the backyard and buried her. She was gone now except for memories that we would hold forever.

“She waited until you were home,” Micah said earnestly. “I think she must have known you were coming back and wanted to see you one last time.”

Years later, we discovered the truth of what happened to Brandy. Brandy, we learned, hadn’t really died in her sleep. She’d died at the veterinarian’s office earlier that morning, with my mother holding her tight as the final injection was administered. Afterward, while we were still sleeping, my mom had brought Brandy back home and placed her in the bed for us to find. She didn’t want us to know that Brandy had been put down; she wanted the three of us to believe that Brandy had died peacefully in her sleep. My mom knew we would have been devastated by the idea of putting her to sleep, and thought it was important to spare our feelings.

Even though we were grown, even though she’d always stressed toughness, she didn’t want Brandy’s death to be harder on us than it had to be.

I had surgery on both my Achilles and my foot in April of my sophomore year. Both my Achilles and plantar fascia (a tendon that runs along the bottom of the foot) had been severely damaged by intensive training. It was touch-and-go as to whether I would ever run again. With the dream still burning, I went through rehab and began jogging in July. By mid-August, I was running without pain for the first time in years. I trained hard and was soon recording the fastest training times I’d ever run in the past; in the second hard workout of the day, for instance, I clipped through five miles in a little more than twenty-three minutes and was never out of breath.

By October, though, the pain was back and getting worse, and I had a cortisone injection at the site of the old injury. An anti-inflammatory, it numbs the area and I kept on running. When the pain came back six weeks later, I got another cortisone shot. Soon, I was getting them monthly, but I salvaged a respectable season nonetheless. By summer, I needed to receive cortisone injections weekly to continue training—I’d had nearly thirty injections since the surgery—and I had to gear myself up for one last season. Both my Achilles and plantar fascia were swollen. As I limped out to the track for a workout, I remember realizing with a sense of clear-eyed finality that I simply couldn’t do it anymore.

I hung up my shoes for good, feeling sadness and—strangely—relief. With the exception of breaking a school record that still stands after nineteen years, I’d failed to reach the other goals I’d set for myself. But despite the fact that running had been the defining force in my life for the previous seven years, I knew that I’d survive without it.

I’d given it my best shot, but it wasn’t meant to be. And if I had to do it all over—and fail to reach my dream again—I would. When you chase a dream, you learn about yourself. You learn your capabilities and limitations, and the value of hard work and persistence.

When I told my dad about my decision—sharing my disappointment as well as relief in knowing that I’d finally made a decision—he put his arm around my shoulder.

“Everyone has dreams,” he said. “And even if yours didn’t work out the way you wanted, it doesn’t make me any less proud of you. Too many people never really try.”

That year, my mom finally got the horse she’d always wanted. A three-year-old Arabian, she named it Chinook.

Chinook was boarded at a stable near the American River, and my mom would drop in to feed and groom the horse before and after work. She could spend hours brushing Chinook’s coat, cleaning her stable, and cleaning the mud from her hooves.

Although there were riding trails along the American River, it was months before my mom could ride her. Chinook had lived most of her life in a pasture (along with a goat) and had never had so much as a saddle placed on her back, which was a big part of the reason my mom could afford to buy her. She was high-strung like many Arabians, but my mom had a natural talent when it came to calming her. Soon, Chinook allowed my mom to saddle her; when she got used to that, my mom finally crawled on. Chinook didn’t seem to like it, but my mom was patient, and I remember the joy in my mom’s voice one day when she called me on the phone.

“I rode Chinook for hours today!” she said. “You can’t believe how wonderful it was.”

“I’m happy for you, Mom,” I said. My mom had lived a life of sacrifice, her own dreams always coming second to ours. I couldn’t help but feel it was finally time that she got something that made her happy.

Later, she would get a second horse named Napoleon. Napoleon was good-natured and even-tempered; the kind of horse that was perfect for my father. And surprising me, my father agreed to go riding as well.

Though my dad was never comfortable in the saddle, I think it was his way of showing my mom that he was willing to work on the marriage. Years of emotional distance had strained their relationship, and Micah sometimes mentioned that he thought my mom had nearly reached the breaking point. Where once she was willing to stay married for the sake of the children, she now sometimes wondered aloud whether she would be happier without my dad. I don’t know if either my mom or my dad ever seriously considered divorce; I do know, however, that my mom spoke the word with increasing frequency, both on the phone and around the house. And my dad, no doubt, had heard her speak of it as well.

Rapprochement is always difficult; when distance has grown over the years, it’s sometimes impossible to overcome. Yet, horseback riding together offered my parents a way to do just that, and little by little my parents seemed to enjoy a budding sense of renewal between them.

My brother continued to live his carefree existence. After graduation from college in 1987, he and a friend went to Europe, and bicycled around Spain, France, and Italy for nearly a month. Upon his return, he shared stories about the adventure before taking a trip to the mountains to go white-water rafting.

In August, he began working full-time as a commercial real estate broker; he continued to date energetically. He brought a different girl home every couple of weeks to meet our parents, and every date seemed crazy about him. In time, my mom called me with the news that he’d brought a particular girl over twice. For Micah, that was just about the closest thing to a steady girlfriend he’d had in years. And when he brought her by a third time, I think my mom knew it was serious.

At Notre Dame, I was edging toward a degree in business finance, with the hope of attending law school after graduation. In March of 1988, a few friends and I decided to drive down to Florida for our final spring break. Because one of my roommate’s fathers owned a condominium on Sanibel Island, we opted to go there instead of the usual destinations like Daytona or Fort Lauderdale.

On our second night there, I noticed a woman walking with a couple of girlfriends through the parking lot of the condominium.

She was attractive—but so was practically everyone after an evening on the town—and she quickly passed from my mind. A moment later, however, when my friends and I had almost reached the lobby, we heard voices calling down to us from the external hallway on the sixth floor.

“Hey, are you guys staying here?”

When we looked up, we noticed the same three girls.

“Yes,” we answered.

“Well, we’re supposed to meet a couple of friends, but they’re not here yet, and we really have to go to the bathroom. Can we use yours?”

“Sure!” we shouted. “We’re on the eighth floor.”

They came up and introduced themselves as seniors from the University of New Hampshire, and we let them in our room to use the bathroom. A moment later, the three of them stood in the kitchen, but my eyes were glued to the woman I had noticed earlier. Up close, she had the most beautiful eyes I’d ever seen, so unusual in color they almost looked unreal. It was all I could do not to stare.

“Hi,” I finally said. “I’m Nick.”

She smiled. “Hey Nick. I’m Cathy.”

I would love to tell you that the initial attraction was mutual, but I’d be lying if I did. The girls stayed in our room for a half hour or so and invited us down to their friends’ place. While we were there, I got their phone number from one of Cathy’s friends and promised to call the next day to see if they wanted to hang out at the beach behind the condominium.

When they decided to join us the following morning, I was palpably nervous about seeing Cathy again. I hoped I’d made a good impression on her, and when I saw her and her friends coming toward us on the beach, I quickly rose to greet them.

“Hey,” I said eagerly, “I’m glad you could come.”

To which Cathy replied, “Oh, hey, I’m Cathy. I didn’t meet you last night, did I?”

Despite the ego bruising, I wasn’t about to be deterred. We ended up talking for hours. When they mentioned that they were going out to a nearby nightclub, I talked my reluctant roommates into going and immediately sought out Cathy. After dancing with her for an hour, I leaned in and said, “You know, you and I are going to get married one day.”

She just laughed in disbelief and said, “I think you need another beer.”

How could I tell so quickly that she was the one for me? It was an odd intuitive moment, but I can honestly say that I knew.

We had a lot in common. Like me, she was a senior who was earning a degree in business. Like me, she was Catholic and went to church every Sunday. She was also a middle child, though one of four. Like me, she had an older brother and a younger sister. Her parents, like mine, were poor before attaining middle-class status, had never been divorced, and—how’s this for coincidence—shared the same anniversary as my parents (August 31). She was an athlete (a state champion in gymnastics). She wanted children, as did I, and she wanted to stay home to raise them, as I hoped my wife would.

But most of all, what really attracted me to her was her manner. She laughed a lot, and it’s easy to fall for someone who can find humor in any situation. She was also intelligent, well read, and well spoken, willing to listen and confident in her beliefs. And most of all, she was warm. She treated my friends as if they’d been her friends for years, would wave and smile at both children and the elderly. She seemed genuinely interested in everyone.

I had noticed all of these things about her, and as we were dancing, it struck me that she was everything I wanted in a lifelong companion.

When I got back to Notre Dame, I called my brother.

“Micah,” I said, “I met the girl I’m going to marry.”

“Where? When? Weren’t you just on spring break?”

“Yeah. That’s where I met her.”

“Dude,” he said, “you were on spring break. What the hell are y

ou thinking about marriage for?”

“Just wait until you meet her.”

“But it was spring break!”

“I know,” I said gleefully. “Isn’t it great?”

In the two months leading up to graduation, I wrote Cathy a hundred letters. She came out to visit me at Notre Dame twice, and on the day of my graduation, my parents came to visit Notre Dame for the first time. While I showed them around the place that had been my home for the previous four years, I talked mainly about Cathy and how much she’d come to mean to me in the previous two months. After graduation, while my parents flew back home, I traveled to New Hampshire to see Cat graduate. I was introduced to her parents, and ten days later I brought her to Sacramento to meet my parents.

My mom and dad greeted her with immediate hugs, and Cathy remained in the kitchen talking to my mom for an hour. That night, after Cathy had gone to bed, my mom declared, “Cathy’s wonderful. She’s even better than you described.”

I thought my heart would burst. “I’m glad you like her, Mom,” was all I said.

After graduation in May 1988, my first thought was, what now?

For years, I’d been a student and an athlete and had pursued those goals with an unwavering intensity. I had done as I was told, I had followed the rules. Yet, all of a sudden, both worlds were behind me, and I found myself adrift. I had no idea who I was, what I wanted to do, or where my future would lead. I’d always believed that because I’d followed the rules the world would beat a path to my doorstep. But the world didn’t seem to care at all.

Despite graduating with high honors, I wasn’t accepted to any of the law schools to which I’d applied, and so that door was closed even before it opened. All my friends had taken corporate jobs in New York or Chicago, but those jobs also tended to be close to the places they’d grown up. I, too, wanted to go home, and with my head filled with foggy notions of the future, I found myself on a plane back to Sacramento. My first job was waiting tables. Even with a degree, I found myself earning minimum wage.

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

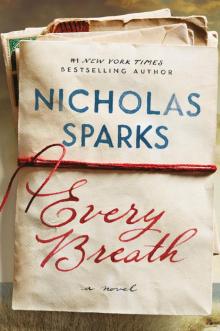

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath