- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

Three Weeks With My Brother Page 16

Three Weeks With My Brother Read online

Page 16

“You’ve always been better,” I said. “You’re the sweetest person I’ve ever met.”

“So what? No one cares about that.”

I took her hand.

“What’s really bothering you?”

She didn’t want to answer. In the silence I looked around the room; like most teenage girls, she had various magazine pictures lining the walls. On her dresser was a collection of bells and ceramic horses. A Bible sat on her end table next to a rosary, and above her bed was a crucifix. It took a long time for her to get the words out.

“Holly got asked to the junior prom.”

Holly was my sister’s best friend; they’d been inseparable for years.

“That’s good, isn’t it?”

When she didn’t answer, my heart sank as I suddenly realized why she was so upset.

“But you’re upset because no one asked you.”

She began to cry again and I slipped my arm around her. “You’ll get asked,” I said soothingly. “You’re a great girl. You’re beautiful and kind, and anyone who doesn’t ask you is too dumb to realize what they’re missing.”

“You don’t understand,” she said. “You and Micah . . . well, all the girls think you’re both cute. They always tell me how lucky I am that you’re my brothers. But it’s hard . . . I mean, no one ever says that I’m pretty.”

“You are pretty,” I insisted.

“No,” she said, “I’m not. I’m average. And when I look in the mirror, I know that.”

She continued to cry, and refused to say anything more. When I finally left the room, I realized for the first time that my sister struggled with the same insecurities everyone had. She had simply been hiding them all along. But as I walked away, I was certain that she’d get asked; I’d meant what I said to her.

But as the days rolled on, and no boy rode up on a horse to be her knight in shining armor, I could see the pain in her disappointed, wounded expression. It killed me to think that no one seemed to realize how special she was, how much love she could offer to anyone who simply asked. I adored my sister in the same way I’d always adored my brother, and—like my parents, I suppose—I felt the need to protect her.

So one evening, about a week before the prom, I went into my sister’s room. If her friends thought I was handsome, if they thought I was popular, then I wanted nothing more than for them to see how much fun we could have together. To me, it made no difference that we were brother and sister; I would be proud to be seen with her and wanted the entire world to know it.

“Dana,” I said seriously, “would you go to the prom with me?”

“Don’t be silly,” she said.

“We’ll have fun,” I promised. “I’ll take you out to a fancy dinner, I’ll rent a limousine, and we’ll dance the night away. I’ll be the best date you’ve ever had.”

She smiled but shook her head. “No, that’s okay. I don’t want to go, anyway. I’m over it now. It doesn’t matter.”

I hesitated, trying to see if she meant it. “Are you sure? It would mean a lot to me.”

“Yeah, I’m sure. But thank you for asking.”

I looked at her. “You’re breaking my heart, you know.”

She gave a sad little laugh. “That’s funny,” she said. “It’s exactly the same thing Micah said.”

“What do you mean?”

“He asked me to the prom, too. Yesterday.”

“And you’re not going with him either?”

“No.”

She wrapped her arms around me and gave me a hug. Then she kissed me on the cheek. “But I want you to know that you two are the best brothers that a sister could ever have. I get so proud when I think about you two. I’m the luckiest girl in the world, and I love you both so much.”

My throat constricted. “Oh, Dana,” I said, “I love you, too.”

CHAPTER 11

Ayers Rock, Australia

February 2–3

Unless you travel over the Pacific, it’s hard to fathom how large the ocean actually is. We’d flown four hours to reach Easter Island, and another seven hours to Rarotonga. Reaching Brisbane, Australia, took another seven hours, during which we crossed over the international date line, and from there we still had another three hours until we finally reached Ayers Rock, in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, in the middle of the Australian outback.

Passing the international date line only served to make the journey longer. It’s an odd feeling to realize that a day seems to have vanished from your life. Not only that, our stop in Brisbane took a couple of hours; all in all, it was over twelve hours en route, which struck me as amazing, considering that we’d already been halfway across the ocean when we started.

By the time we got to our hotel, everyone wore the look of weary travelers. In the lobby, it was possible to sign up for excursions the following day. While everyone would go to Ayers Rock in the afternoon, the morning was open. You could rent Harleys, for instance, and explore parts of the outback on your own, or take a helicopter ride over the Olgas—an outcropping of rock and canyons near Ayers Rock. There was also a walking tour through part of the Olgas as well, and a sunrise trip to Ayers Rock, which would leave the hotel before dawn.

Though my brother and I wanted to sleep, we somehow woke in time to join the sunrise expedition party. It was cool and pitch black in the desert; without lights, it was possible to see tens of thousands—if not millions—of stars. Our bus was one in a long line of buses that made their way out there that morning; we later found out that our hotel was large enough to room over three thousand guests. While this may not mean much in a city like Orlando or Chicago, in the middle of the outback, it’s amazing. At any given moment, we learned, the hotel itself had a higher population than nearly every city for hundreds of miles in any direction.

Ayers Rock is the largest monolith, or single-unit stone, in the world. With a circumference of nearly five miles, it rises nearly a thousand feet in the air, and extends over three miles beneath the surface. In the predawn blackness, Ayers Rock was nothing but a darkened shadow, almost impossible to see unless you were looking directly toward it. Our disheveled group stumbled out of the bus and we made our way to the viewing area.

In time, light began glowing over the horizon, and as it slowly began to spread, our gaze was directed to the rock. Comprised of coarse-grained sandstone rich in feldspar, Ayers Rock was supposed to vary in color depending on the time of day and atmospheric conditions. Still, in the beginning anyway, it was difficult to understand why so many people found it fascinating; it had none of the fiery brilliance for which the rock had become famous. My brother and I took pictures, then more pictures, feeling disappointed. Soon, however, the sun rose high enough to brighten the eastern sky, and just when we came to the conclusion that the reputation of Ayers Rock was more hype than reality, it suddenly happened.

The sun hit the rock at such an angle that it began glowing red, like an enormous glowing coal. And for the next few minutes, all Micah and I could do was stare at it, thinking it was one of the most amazing things we’d ever seen.

Micah and I had opted for the helicopter ride instead of a walking tour through the Olgas, and by eight A.M. we were at the airport again, ready to depart.

There was, we learned, a good reason for taking the ride as early as we did. It was already hot by the time we arrived—it was summer in the desert, after all—and the canopy of the helicopter served only to intensify the heat. With five people crowded inside, everyone was sweating within moments of liftoff.

We were in the air a little more than thirty minutes, but it afforded us views impossible to see any other way. We circled Ayers Rock and flew over the Olgas; we spotted wild camels trailing through the desert. There were, we learned, tens of thousands of wild camels in Australia. They were nonindigenous—originally, they’d been imported for their survival skills to help settle the outback. A few had escaped and flourished; over time, the population had swelled. Nowadays, they were actual

ly exported back to the Middle East.

Because of the rotating blades and the roar of the engine, conversation was impossible. But whenever I happened to glance back at Micah, I noticed that he never stopped smiling.

Once we returned from the helicopter ride, we had some free time until lunch, and we decided to go for a jog around the property.

With thousands of miles logged on our legs over the course of our lifetimes, jogging felt natural to both of us. Falling into a moderate clip, our strides quickly became synchronized.

“This is like old times,” I said. “When we were back in high school.”

“I was just thinking the same thing.”

“How often do you jog these days?”

“Not too much,” Micah answered. His breaths were even and steady. “I run when I play soccer, but if I try to do it every day, my back gets sore.”

“I know what you mean. I used to run a fast twenty miles on Sundays, but these days I can’t even imagine it. If I go four miles, I feel like I’ve really accomplished something.”

“That’s because we’re getting older,” he said. “Do you realize my twenty-year high school reunion is coming up in a few months?”

“Are you going?”

“I think so. It’ll be fun to see everyone. But when I think of high school, I think about Mike, Harold, you, and Tracy. Now those were great times.” For a while I listened to the sound of our feet on the compact dirt. “Do you remember when you and Harold went out on a double date that one time? When Tracy and I found you and had you roll down the car window so we could launch a bottle rocket into your car?”

I laughed. “How could I forget?” The thing had exploded at our feet, scaring the daylights out of us.

“Yeah, those are the memories that stay with me,” he said. “Those guys were great, and they’re the only ones I still really talk to anymore. It’s hard to believe that it all happened twenty years ago.”

After lunch and a shower, we headed back to Ayers Rock with the rest of our group. By then, the glare was relentless. It was over a hundred degrees, and with the sun high overhead, Ayers Rock was sandstone, its color unremarkable. Flies swarmed everywhere; you had to move continuously or they’d land on your lips or eyelashes, your arms and your back. There were trillions of flies. The tourists looked as if they’d taken wiggle pills.

Over the next few hours, the bus stopped in various places around Ayers Rock, which is regarded as sacred among the aborigines. We’d head out, walk around, listen to a story, then head back to the bus. We were led to some painted caves and a watering hole, where we were exposed to endless lectures about aboriginal history.

At the third or fourth stop, I turned to say something to Micah. His eyes were glassy and unfocused. At that point, we’d been listening to a story concerning one of the upper crevices on the rock. It had to do with a spirit warrior who got lost in the desert, only to fight a battle with another spirit, and somehow the images of the battle had been imprinted on the rock. This, in turn, led people to know where the watering hole was; they would search the rock for said image, thereby knowing they were close. Or something like that. The blistering heat was making me dizzy and it was difficult to keep all the characters in the legend straight.

“Have you ever noticed that the less interesting something is, the longer people want to talk about it?” Micah sighed, slapping at the buzzing flies.

“C’mon, it’s interesting. It’s a culture we know nothing about.”

“The reason we don’t know anything about it is because it’s boring.”

“It’s not boring.”

“It’s a big rock in the middle of the desert.”

“What about the colors?”

“We saw the colors this morning. In the daytime, it’s a big rock. And I wasn’t being eaten by flies or cooked in the sun while being subjected to endless stories about spirit battles.”

“Doesn’t it amaze you that people could actually survive out here for thousands of years?”

“It amazes me that they never left. What? You mean no aborigines ever wandered to the coast, saw the beaches and felt the cool breezes while catching fish for dinner, and said to themselves, ‘Hey, maybe I should think about moving?’”

“I think the heat’s getting to you.”

“Oh yeah, it’s getting to me. I’m dying out here. I feel like buzzards are overhead, just waiting for me to drop my guard.”

Late in the day, we headed back to Ayers Rock for the third time. This would be our chance to see how it changed colors at sunset.

“I’m beginning to get the impression that there’s not much to do around here besides stare at Ayers Rock,” Micah confided.

“It won’t be so bad,” I said. “I hear there’s supposed to be original aborigine music tonight.”

“Oh, gee,” he said, throwing up his hands. “I can’t wait.”

As it turned out, that evening was one of the trip’s most memorable. It began with a cocktail party—and yes, everyone stared at Ayers Rock when the sun started going down—but afterward we were led to a small clearing where tables had been set up, complete with white tablecloths, candle centerpieces, and beautiful floral arrangements; the setting was gorgeous and the food delicious. Among other things, on the buffet they had both kangaroo and crocodile meat, simmered in spices and cooked to perfection. The temperature cooled, and even the flies seemed to have vanished.

We ate in the desert under a slowly blackening sky; in time, the stars appeared in full. Later, the candles were blown out and an astronomer began to speak. Using a floodlight to point to various areas of the sky, she described the world above.

Not only was it dark and clear enough to make out individual stars in the vast sweep of the Milky Way, but because we were in the Southern Hemisphere, the sky was completely foreign to us. We were all spellbound. Instead of the Big Dipper and Polaris (the North Star), we saw the Southern Cross, and learned how sailors used it to navigate. Jupiter was closer to Earth than it had been in decades, and glowed bright in the sky. Saturn, too, was visible, making it the first time I’d ever seen both planets in the same sky. Even better, we found out that TCS had made arrangements for telescopes. That evening, I saw the moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn, and while I’d seen them in books I’d never seen them through a lens. It was a first for Micah, too.

On the way back to the hotel, he leaned his head back on the seat, the picture of contentment. “The morning was great, and the evening was the best on the trip so far.”

“It’s just the middle you could have done without, right?”

He smiled without opening his eyes. “You’re reading my mind, little brother.”

I leaned my head back and closed my eyes as well. No one on the bus was speaking; most seemed as relaxed as we were. In the silence, my mind wandered. The years had passed so quickly that I couldn’t help but feel as if my life seemed surreal, almost like I were viewing it through someone else’s eyes. Perhaps it was because of the evening I’d just spent, or maybe it was due to exhaustion, but in the midst of this foreign land I suddenly didn’t feel like a thirty-seven-year-old author, or husband, or even a father of five. Instead, it almost seemed as if I were just starting out in the world and facing an uncertain future, similar to how I felt when I first stepped off the plane in South Bend, Indiana, in August 1984.

My first year at Notre Dame proved to be a challenge. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t the smartest kid in class, and my studies were much harder than I imagined they would be. I studied an average of four hours a day and didn’t do nearly as well as I’d hoped; over the next four years, the number of hours I studied would only increase.

I found it hard to be away from home. I missed my family and friends, I missed Lisa, and I didn’t get along with my new roommate. Worst of all, the second week after I arrived, I strained my Achilles tendon, tried to train through the pain, and got a raging case of tendinitis. My Achilles swelled to the size of a golf ball. Acc

ording to the doctors, the only thing that would allow it to heal was to stop running entirely.

By that point, running was the most important thing in my life, and the idea of not running was counter to everything I believed in. My dream was to follow in Billy Mills’s footsteps; to represent the United States on the Olympic team and win the gold medal. I know now that even had I never been injured, the dream was an unattainable one. I might as well have wished to fly.

As I said, I was a good runner, but not a great one. I didn’t have the natural foot speed or stamina to be world-class; indeed, I’d gotten as far as I had by training harder than most high schoolers. These realizations were only made in retrospect; at the time, the injury was devastating to me. For the first time in my life, I felt as if I were failing.

The injury raged on throughout the fall; in the winter it healed slightly before I reinjured it again. Around that time, Lisa and I broke up, high school sweethearts doomed by the distance between us. School continued to be a challenge, in part because my mind was elsewhere.

I somehow managed to scrape together a partial outdoor season, and even ended up breaking the school record as a member of one of the relay teams. It was my last meet of the year. By the time I finished the race, I could barely walk. My Achilles tendon had swollen to the size of a lemon. Any movement was excruciating; my tendon literally squeaked like a rusty hinge whenever I took a step. When I arrived back home for my summer break, I needed crutches to get off the plane.

I was miserable for the first few weeks of the summer. I had no job, no girlfriend, and because my brother had moved out, no one to hang around with. In addition, I was under doctor’s orders not to run for three months, which would only put me further behind my peers.

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

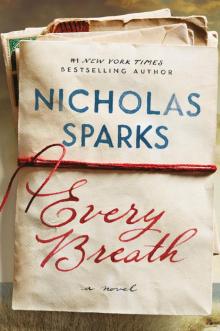

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath