- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

Three Weeks With My Brother Page 31

Three Weeks With My Brother Read online

Page 31

Less than two weeks after my sister’s funeral, I began to work on A Bend in the Road, a story inspired by my brother-in-law, Bob. It was the story of a young widower with a child, and I forced myself to sit at the computer for days on end to finish it. That fall, I toured in Europe and the United States to promote The Rescue, and as soon as the edits on A Bend in the Road were completed in early 2001, I began The Guardian, which would eventually become my longest and most challenging book to date. Little by little, work on the novel began to consume me.

I’d become so used to stress in the last eleven years that it was as if I didn’t know how to function without it, and from that point on I continually added more to my plate. In January 2001, we found out that Cat was pregnant again; a few months later we learned she was having twin girls. After three boys, it was definitely exciting, and expecting twins seemed appropriate considering the sudden increase in the pace of life.

I became the master of scheduling. Every minute was planned for during the course of a day. Time was not to be wasted, even when I didn’t work, for my responsibilities didn’t end there. To accomplish everything, I compartmentalized my life into little boxes: If I wasn’t working, I was dad, or husband, and I focused on those areas as intensely as my work. In the same way I sought my parents’ approval, I sought my family’s. I couldn’t be simply dad, I tried to be super-dad: I coached soccer teams, attended gymnastics practices, helped with homework, played catch, and spent the weekends boating, bowling, swimming, and heading to the beach. I continued working with Ryan informally—he no longer needed intense structure—and played on the carpet with Landon every night. I tried to be the best husband I could, helping around the house, and doing my best to romance my wife. Somehow, despite all that, I squeezed in time to earn a black belt in Tae Kwon Do, lift weights, and jog daily. I continued to read a hundred books a year.

I slept less than five hours a night.

It wasn’t all bad news, however. In the spring of 2001, I picked up the phone to hear Micah’s excited voice.

“Christine is pregnant,” he said. “We just found out.”

“Congratulations,” I said sincerely. “When’s the baby due?”

“January,” he said. “Just like Landon. And the twins will be only a few months old when she’s born, so they’ll have fun as cousins when they get older. When are the twins due?”

“Late August. How’s Christine holding up?”

“Great, so far. She wouldn’t have even known that she was pregnant except for the home pregnancy test she took.”

“That’s wonderful,” I enthused. “I’ll tell you, though—it’s going to change your life.”

“I know. I can’t wait.”

“You ready for this? Being a father?”

“Of course I’m ready. I’ve raised Alli since she was two.”

“That’s when they start getting easy. Wait until there’s a newborn. It’s a whole different world.”

“Any words of advice you want to offer? Since it’s my first time, and you’re the expert?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Toward the end of the pregnancy, see all the movies you can.”

“Why?”

“Because,” I said, “you’re not going to see another movie for at least a year.”

“Yeah, we will. Christine loves movies.”

“Trust me,” I said. “Nothing can change a lifestyle more than having a baby.”

“Yeah, yeah,” he said. Despite myself, I smiled inwardly. He’d learn soon enough.

“And Micah?”

“Yeah?”

“Congratulations again. Everything changes, but it’s a change for the better.”

“Thanks, little brother.” He paused. “Oh yeah, one more thing—Cat wanted me to tell you this.”

“What’s that?”

“Quit working so hard.”

“I will when you start going to church again.”

We both laughed.

“This is great,” I said. “I’m happy for you and Christine.”

“Me, too.”

I didn’t listen to my brother. Or to my wife.

By early summer 2001, one year after my sister’s death, Cat was heavy with twins, and I had to take on even more responsibility, since she couldn’t keep up with the toddler or the older boys. To meet those additional demands on my time, I found myself sacrificing more sleep. Throughout that summer, I averaged less than three hours a night, and though I felt like a zombie when I stumbled out of bed, I quickly poured a cup of coffee, and charged into my day.

And I went and went and went. Working. Watching the kids. Taking care of Landon. Cleaning the house. Go, go, go.

Somehow, I was pulling it off. But a pace like that isn’t normal, nor is it realistic. Something had to give, and for me, it was not only sleep, but simple downtime during the day. No lazy mornings sleeping in, no poker games with friends, no time to watch sports on television. I rushed through lunch and dinner. For a while, it didn’t bother me, for my schedule made it seem as if I were in control of my life. I was taking care of all that I needed to. The schedule, though, had begun to control me. Little by little, I forgot how to relax. Even worse, I began to feel as if I didn’t deserve to relax. Not until I finished ——— (fill in the blank).

But nothing was ever finished. There was always one more page to write, one more novel to finish, one more city to add to a tour, one more interview to give. My children continued to need my attention, no matter how much time I spent with them the day before. There was always another chore around the house. I wasn’t necessarily unhappy—boredom has never suited me—and the pace wasn’t killing me physically. But the lack of downtime, I would eventually realize, wasn’t good for me mentally or emotionally. I began waking every day with the sense that I was falling behind. Despite my best efforts, I began to feel as if I were failing. Where once I was doing all those things because I wanted to, it gradually came to feel as if I had to, as if I had no other choice.

I say this in retrospect. At the time, I couldn’t see the forest for the trees. Back then, all I knew was that I began to wake up with a sickening sense of dread. As soon as my eyes popped open, my mind filled with all that I had to do, and how my only chance to get it done was to start right then, at that moment, and get going. My life was a long to-do list, and instead of slowing down and doing what I could, I’d roll up my sleeves, grit my teeth, and work even harder.

Again, I wasn’t consciously unhappy about it. I tried to find humor in the situation. I continued to laugh. People often remarked at how optimistic I seemed or how much I smiled. Yet, slowly but surely, life was becoming a grind, and there was nothing I could do to stop it.

My brother and I continued to speak on the phone regularly that summer. Our conversations—after discussing our pregnant wives—usually went as follows:

“What’s going on?” he might ask, and I’d begin telling him everything I had scheduled. When I finished, he’d say nothing for a moment.

“So when do you sleep?” he’d ask.

“When I get the chance,” I answered. Strangely, I felt a sense of pride about this, as if this were an admirable quality.

“That’s dumb,” he said. “You gotta sleep. And you gotta take time for yourself, too. You’ll go crazy if you don’t. Haven’t you learned the importance of balance yet? Life is all about balance, and right now, your life is seriously out of whack.”

“I’ll be fine.”

“Well, you sound stressed.”

“Just busy. I’m fine—really,” I said. “So what’s going on with you?”

“Just living my life. I get up whenever I want and linger over the newspaper. I work out for a while, get in the shower around noon, and then figure out what I want to do next.”

“Must be nice.”

“You could do it, too. Everyone chooses his own life.”

“Not always,” I said. “Sometimes responsibilities get in the way. Granted, I could choose to ignore them, but

it wouldn’t be good for my family.”

“Your family will be fine. You’re just making excuses. You’re going to go crazy if you keep up like this.”

I didn’t see it that way. I knew, however, there was no use arguing with him.

“Enough about me. How are you doing?”

“The same.”

“You going to church yet?”

“Not really.”

“How’s Christine handling it?”

“The same. She’s not too happy about it.”

“Don’t you think you should go then? If only for her?”

“You go to church for yourself, Nick. If you go for someone else, it doesn’t mean anything.”

“Then go for you.”

“I’m not in the mood right now. I’ve got nothing against it, but I’m not getting anything out of it when I do go. I feel like a hypocrite sitting there.”

“You can always use the time to pray.”

“I’ve tried praying. I prayed for Dana every day, and she still died. Praying doesn’t work.”

We acknowledged our standoff with a moment of silence before Micah cleared his throat.

“So how’s Ryan doing?”

In early August 2001, my brother was proven correct.

Endless nights of allowing myself only three hours of sleep had left me exhausted, and something inside me finally gave way. It came out of the blue. I woke with a feeling of anxiety unlike anything I’d ever experienced. I couldn’t concentrate, and all of a sudden I started crying for the first time since my sister had died. I simply couldn’t stop. My wife—now approaching her thirty-fifth week of pregnancy—held me in her arms, then sat me down.

“You need a break,” she said. “Go to the beach house for a couple of days. I’ll be fine here.”

“Yeah . . . okay . . . let me get my things . . .”

She put her hand on my computer. “This stays here,” she said. “I want you to relax. Take long walks by the water, sleep in. Do absolutely nothing for a few days.”

My first night there, I slept seventeen straight hours. When I woke, I read for a little while, then slept another nine.

My brother called me a few days later.

“Heard about your little breakdown,” he said. “I told you it would catch up to you.”

“You were right.”

“How you doing now?”

“Better,” I said. “I think I was just tired and needed sleep.”

“I think you need to learn to slow down.”

“Like you?”

“Hey,” he said, “I’m not the one who crashed. And in fact, I think I’m ready to go back to work. I’m starting another business.”

“Doing what?”

“Same thing,” he said. “Making garage cabinets.”

“Good for you.”

“Yeah, I’m excited about it, and with Christine pregnant, it’s time. Besides, I’ve been getting bored lately. All my friends are working. No one has time to do anything fun.”

Despite myself, I laughed. “Imagine that,” I said.

In the fall of 2001, despite the lessons I should have learned, I threw myself back into work with a vengeance. If anything, I grew even busier than I’d been before.

Savannah and Lexie were born on August 24; Lexie Danielle had been named for my sister. While my wife took care of the twins and recovered, I took care of the other three kids and the household, at the same time pushing myself to finish the novel. A month later, I was on the road touring the country for A Bend in the Road. My wife, with twins, a toddler, and two older sons, somehow managed to keep the household running smoothly.

But again, there was more. There was always more.

At birth, Lexie had a small hemangioma—a collection of excess blood vessels in the soft tissue beneath her chin. It was the size of a pencil eraser at birth; by the time I went on tour for A Bend in the Road, it was a bulbous, purple mass that made her chin seem small in comparison.

It ruptured while I was on tour. Cat and I were talking on the phone, when she suddenly screamed, “I’ve got to go! Lexie’s chin is gushing blood!”

Lexie was seven weeks old when she was rolled into surgery; that night, I signed books for eight hundred people, hating myself for not being with my family.

But still, I continued to work like a demon. I finished the first draft of The Guardian while in Jackson, Mississippi, and as soon as I got back home, I wrote a screenplay based on the same novel. I then composed text for a Web site that had more words than my first novel. In my spare time, I began working on a television pilot based on The Rescue for CBS, agreeing to serve as an executive producer if the network picked it up. Then, in late December 2001, I heard from my editor.

The Guardian, I was told, would need extensive revisions—including a complete rewrite on the last half of the book—and I couldn’t imagine having to start all over on the novel. Yet, with a deadline looming, I needed a novel for the coming fall. Instead of reworking the novel, I began writing Nights in Rodanthe, to be published that fall in its place. The Guardian, my publisher and I decided, would be published in spring 2003, and I would edit it when Nights in Rodanthe was completed. While the time pressure on Nights in Rodanthe was intense—it had to be completed by April—it meant I had to do something else as well; namely I would have to write a third novel that year, immediately after finishing The Guardian, to be ready for fall 2003. The preliminary title was The Wedding.

In other words, 2002 was shaping up to be even busier than the previous year. Not only did I have five children and a wife—all of whom needed time and attention—but I’d have to work harder and faster than I ever had, simply to get it all done. It was still doubtful, though, I’d be able to finish before the year was out.

But by then, it didn’t matter. I’d been running so hard, I didn’t know how to stop. Life became something to conquer, rather than live, and had I wanted to change, I couldn’t have figured out how to do it. Even then, however, I think I subconsciously knew that I needed to get my life back into balance, and that only Micah could help me do that.

And, as if my prayers were finally answered, it was around this time that the brochure came in the mail.

EPILOGUE

Heading Home

Saturday, February 15

On our last night in Tromsø, we had a farewell dinner. It was an early night. We would be departing first thing in the morning, and because of a two-hour layover in England, the flight home would take nearly fifteen hours.

The atmosphere on the plane varied from boisterous to quiet. People mingled in the aisles, continuing to exchange phone numbers and e-mail addresses. Micah and I said our good-byes as well; once we landed and got through customs, everyone would head off in different directions to catch their final flights back home.

Later, while Micah was napping, I gazed out the window, watching the clouds pass beneath us.

I wasn’t sure how I felt. Part of me was sad that our adventure had come to an end; another part was thrilled at the thought of seeing my wife and kids. Cat and I have loved each other since the third week of March 1988, and my feelings for her have grown only stronger over the years. How could they not? We were married only six weeks when catastrophe first struck, and she was the one who held me on those first few terrible nights, when everything always seemed hardest. And she’s never stopped holding me since. As hard as it’s been, as heartbreaking as it’s been, I know that in many ways I’ve been fortunate. My wife and children are proof of that. And even now, when I pray at night, I find myself thanking God for all the blessings in my life.

At heart, I suppose, I’m an optimist like my mom was. Granted, an optimist who sometimes worries too much or works too hard, but an optimist nonetheless. In those moments when I feel sad about the loss of my parents and my sister, I’ve found that if I look closely at my children, I see hints of my own past. In my family growing up, there were five of us; three males and two females. Among my kids, those numbers are ex

actly the same, and I’ve come to realize that as the echoes of my own family’s voices gradually dim over time, they’ve been replaced by the excited sounds of happy childhood. As they say, the circle of life continues.

The lessons my parents taught are still with me. I keep a tighter leash when raising my kids than my parents did, but I often find myself doing or saying the same things they did. My mom, for instance, was always cheerful when coming in from work; I try to behave the same way when I finish writing for the day. My dad would listen intently when I came to him with a problem, to help me find a way to solve it on my own; I try to do the same with my own kids. At night, while I’m tucking my kids in bed, I ask them to tell me three nice things that each of their siblings did for them that day, in the hopes that it will help them grow as close as Micah, Dana, and I did. And more frequently than I ever would have imagined possible growing up, I find myself telling my children It’s your life, or No one ever promised that life would be fair, and What you want and what you get are usually two entirely different things. And after I say these words, I turn away and try to hide my smile, wondering what my parents would think about that.

When my thoughts turn to Dana, though, it’s not easy. Her death sent me into a tailspin of sorts, one that took years from which to recover. She was too young, too sweet, too much a part of me for me to accept that she’s gone. Yet my sister taught me well. Alone among the family, my sister never let her illness get her down, and I’ve tried to learn from her example. She lived her life fully despite her fears; she laughed and smiled until the very end. My sister, you see, had always been the strongest among us all.

“What are you thinking about?” Micah asked. Waking from his nap, he stretched in his seat.

“Everything,” I said. “The trip. Our family. Cat and the kids.”

“Did you think about work?”

I shook my head. “Actually, I didn’t.”

“But you’ll plunge back in as soon as you get home, right?”

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

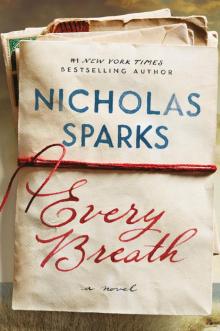

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath