- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

Three Weeks With My Brother Page 21

Three Weeks With My Brother Read online

Page 21

The nurse continued to move the scope, trying to get a better picture; within a few moments, both Cathy and I saw the technician frown.

“What is it?” Cathy asked.

“I’m not sure yet,” the technician answered. She forced a smile. “Could you excuse me for a moment?” The technician got up and left the room.

We didn’t know what to make of it; we had no idea whether this was normal or unexpected. A couple of minutes later, the doctor came in.

“Is anything wrong?” Cathy asked.

“Let me take a look,” the doctor said. For a moment, as the technician began working the scope, we watched them both staring at the screen. The technician pointed and whispered something to the doctor. He whispered something back. Neither would answer our questions; in time, the technician rose and left the room. The doctor looked serious.

“Something’s wrong, isn’t it?” Cathy asked.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “But we can’t find a heartbeat.”

Cat burst into tears; eventually, I led her from the office. Our baby had died, just as my mother had, for no apparent reason at all. A few days later, Cat had a D&C. In the wheelchair after the procedure, all she could do was wipe her tears; there was nothing I could say to ease her pain.

Later, in Micah’s arms, I cried as well.

Cat and I spent the next few months worrying about the possibility of becoming parents. We didn’t know how long it would take for her to get pregnant again, nor did we know whether she could carry a baby to term. We’d been told that miscarriages were common; everyone seemed to know someone who’d had one and tried to console us with the thought that everything would be fine in the long run. We knew they meant well, we knew what they were saying was true. But we also were well acquainted with the other kind of story, the kind where things didn’t work out, and to Cat, the thought of never becoming a mother was unbearable. Another hard Christmas came and went, and on my birthday, when I turned twenty-five, my sister called to sing me “Happy Birthday.” When she asked me what I wanted, I could think of only one thing to say.

Our prayers were answered again in late January 1991, but we kept the news to ourselves this time. We didn’t want a repeat of what had happened before, but in April we learned the baby was developing normally and finally shared the good news. Cathy’s belly grew over the summer, and she spent hours looking through baby-name books and reading What to Expect When You’re Expecting.

Yet the stresses of life seemed to keep coming, one after the other, without relief. Despite working two jobs—three if you count Cat’s job—we were still struggling financially, unable to get ahead. Cat had health insurance through her employer, one that covered maternity, but in early summer, while she was five months along, she was laid off. When our cocker spaniel puppy reached twenty pounds, we were evicted from our apartment and had to find a new place to live. Our one car broke down completely, and the only car we could afford as a replacement was thirteen years old and had a hundred thousand miles on the odometer. The IRS decided to audit both my business and my personal tax returns concerning the previous three years; though I would eventually be cleared completely, the stress of working two jobs while collecting the necessary documents—they wanted receipts for everything—added to an already difficult summer.

Somehow I was able to squeeze in time to write a book with Billy Mills, entitled Wokini. Though it would end up being the first work I’d ever publish, I was under no illusions that it had to do with the quality of my writing. Rather, its merit derived from who Billy was.

In September, we rushed to the hospital when labor pains began. It was a fast labor; Cat dilated quickly, and was nearly ready to deliver by the time we reached the hospital. Cat was in back labor—the baby was facing the wrong way—and in immense pain. There was a mad scramble as the room began to be readied, but moments after the doctor arrived, the baby’s heart suddenly slowed.

By the looks on the doctor’s and nurse’s faces, I knew it was serious. There was a chance we would lose another baby.

All at once, the world seemed to shrink; all I could think about was Cat and the baby she carried inside her. There is a panic that comes in moments like those, one that squeezes the heart with a feeling of utter helplessness. I barely remember the heated rush of activity as the doctor swung into action; I stood off to the side, praying as I’d never prayed before.

The doctor was good, and a moment later I was a father. But the baby’s skin was gray, and for the longest moment, he made no sound at all. Later, we’d learn that he was anemic and that he’d bled back through the umbilical cord. But at the time, I simply wanted to hear the cry of life.

And then, after what seemed like forever, I finally did.

Within a few minutes—minutes that seem far longer when it’s actually happening—the doctor assured us our son would be fine, and for the first time I relaxed enough to realize that we’d actually become parents. Cat held the baby against her. We named him Miles Andrew, and the first person I called was Micah.

“I’m a father!” I screamed into the receiver. “I have a son!”

Micah whooped on the other end. “Congratulations, Daddy! How’s mama doing?”

“She’s doing great—and thankfully the baby is, too. But you’ve got to get down here! You’ve got to see this little guy! He’s so cute!”

He laughed again. “I’m on my way, little brother. I’m on my way.”

He was the first one to reach the hospital, and after taking one look at Miles, he turned to me.

“Why, he looks just like me.”

I slapped him on the back. “You should only be so lucky. You might be handsome, but you don’t hold a candle to this guy!”

Despite the new life of fatherhood I was suddenly leading, my brother and I continued to make time to be together. For a short while, he helped me with my orthopedic business, but by the end of the year I eventually decided to give it up. With a new child at home, I needed something more stable, and I took a job as a pharmaceutical representative with Lederle Labs in early 1992. It was the first time in my life in which I’d officially be earning above minimum wage. I was twenty-six years old.

But if the baby—and my radically transformed life—was enough to help me keep from dwelling on mom, my dad continued to experience intense periods of ups and downs. The good mood he’d had over the summer was replaced with a funk, then replaced again with optimism. It had reached the point where we didn’t know what to expect when we went to see him, and both Micah and I wondered aloud whether he was manic-depressive.

My sister, too, seemed to be having a rough time, struggling to find herself as many young adults do. Never a great student, she dropped out of college to work full-time, then proceeded to quit her job a couple of weeks later. From there, she wandered from one job to the next, working as a cocktail waitress, an aerobics instructor, a receptionist at a tanning salon. She and Micah got separate apartments again, and my dad helped her with the rent. Physically, she was changing as well. By her early twenties, she’d become something of a beauty. She was quite popular with the opposite sex all of a sudden, but like Micah, she seemed to move quickly from one relationship to the next.

“What is it with you two?” I asked Micah one night.

“What do you mean?”

“You and Dana. Can’t either of you date anyone for longer than a month?”

“I dated Juli and Cindy for years.”

“Half the time you say you were dating them, you were actually broken up, and you were dating other people. And then you ended it with both of them.”

He smiled. “Not everyone wants to be married at twenty-three, Nick.”

“I didn’t plan to marry that early. It’s just that I met Cathy.”

“You didn’t have to marry her right away.”

“Yes I did. Do you know what she said to me when she decided to move to California? While I was picking her up at the airport?”

He shook his head.

“When I met her at the airport, I started telling her all this really sweet stuff—you know, how much I loved her, how glad I was that she’d moved out here, how much I appreciated her courage. Anyway, she let me finish before she finally smiled.

“‘I love you, too, Nick. And I’m glad I came. But let’s get one thing straight. As much as I love you, I’m not going to abandon my family for a relationship that might be only temporary.’ So what does that mean? I asked her, and she patted my chest. ‘You’ve got six months to propose, or I’m going back home.’”

Micah’s eyes widened. “She said that?”

“Yep.”

He laughed. “I love that girl. She doesn’t take guff from anyone, does she?”

“Nope.”

“You did the right thing, Nick. You couldn’t have married anyone better.”

“I know. But as I was saying earlier—what’s with you?”

“It’s simple, Nick,” he said. “I haven’t met my Cathy yet. But when I do, I’ll marry her and settle down.”

By 1992, three years after my mom had died, each of us had somehow found a way to move on. I had a family and a new career; Dana had a new boyfriend and was back in college. Micah continued to date and enjoy one exciting weekend after the next. Though dad was still wearing black, the ups and downs were getting less frequent, and he’d even begun to think about dating again. Our family life, as much as could be expected, was gradually regaining some semblance of normalcy.

In October, Cathy and I eventually came to the conclusion that it would be best if we moved away. While we loved California, practicalities precluded us from being able to create the kind of family life we wanted for our son. My salary, while decent, wasn’t enough to enable us to live in the kind of neighborhood Cathy wanted for Miles. Nor, due to rapidly escalating housing costs, could we foresee a change in the future.

What Cat and I wanted, I suppose, was the chance to live the American dream. We dreamed of having a house we could call our own, a decent-size yard for the kids, a barbecue grill in the backyard. Just the basics, but the basics were out of reach, and after a series of long discussions with Cat, I finally talked to my boss about applying for a transfer to a territory in the southeast. My boss wasn’t thrilled by my request; I’d only been with the company for eight months, had only recently completed all my training, and was doing well in my territory. He didn’t want to go through the process of hiring someone new, since there was always a risk the new employee wouldn’t work out. And, of course, the territory would suffer while a new employee was being trained.

That night, I called Micah.

“Micah,” I said, “do you want a job selling pharmaceuticals?”

My proposal made perfect sense to me. We’d run together, waited tables together, owned houses together, and he’d been part of the small company I’d started as well. We even looked somewhat alike.

For a moment, Micah was taken aback. Though he’d done well in real estate, it was strictly commission work, and was dominated by the large brokerage houses. Because he was with a smaller firm, finding new listings required endless hustle, and he’d grown tired of the way his firm dragged out paying him what he was owed.

“What do you mean?” he finally asked.

“If I get the transfer, I’ll introduce you to my boss, you can interview with him, and I bet he’ll hire you.”

“You think so?”

“I know so.”

He thought about it overnight and called me the next morning.

“Nick,” he said. “I think I want to be a pharmaceutical rep.”

And lo and behold, after I received a new territory centered in New Bern, North Carolina, my brother was hired, took over my old territory in Sacramento, and I handed him the keys to my company car.

Meanwhile, Cat and I began the process of getting ready for a new life on the other side of the country.

In early November, less than a week after Micah accepted the job, I was at home and beginning the slow process of packing up our things when I got a frantic call from my father.

“You’ve got to get to the hospital right now,” my father suddenly said. He was breathless and scattered, a reprise of that fateful call three years ago. “She’s at Methodist. Do you know where that is? Bob just brought her in a couple of minutes ago.”

Bob, I knew, was Dana’s boyfriend, but my dad’s garbled message didn’t make sense.

“Who? Are you talking about Dana? Is she okay?”

“Dana . . . she’s in the hospital . . .”

“Is she okay?” I repeated.

“I don’t know . . . I’ve got to get down there . . .”

My head suddenly began spinning with a sense of déjà vu.

“Do you know what happened? Was she in an accident?”

“I don’t know . . . I don’t think so . . . Bob said she had a seizure of some sort . . . I don’t know anything else . . . Micah’s on his way . . . I’m heading there now.”

At the hospital, Bob told us what had happened. Bob lived on a ranch in Elk Grove and worked as a local trucker delivering feed for horses and cattle. Taller and heavier than Micah or me, he wore cowboy boots and had competed in bareback rodeo riding. I’d never seem him look as frightened as he did at that moment.

“She woke up and she couldn’t talk right,” he said. “Her words were all mixed up, and she didn’t make any sense. So I loaded her in the car, and we started for the hospital. On the way, her eyes rolled back, and she started to convulse. She was still having the seizure when we got here. They took her back, and I haven’t seen her since.”

Though a different hospital, it was eerily reminiscent of the one where my mother had died. So were our feelings as we paced the small corridor, waiting to hear what was going on. And so was the room where we eventually saw my sister.

Dana was tired when we saw her; she’d been given medication for the seizure, and her eyes drooped. She, like us, was frightened, and she knew no more of what had happened to her than we did. But other than exhaustion, she seemed fine. She could tap the tips of her fingers against her thumb, she could remember everything from the night before. And she remembered realizing that something was wrong when she woke up earlier that morning.

“I remember trying to talk,” she said, somewhat groggily. “I can even remember hearing the words coming out, but they were the wrong words. So I’d try to repeat myself, and the same thing happened again. And the smell. I kept smelling something really bad. That’s when Bob put me in the car. I don’t remember anything after that, though.”

Later, the doctor said she had had a grand mal seizure, though when pressed, he wouldn’t speculate as to the reason until further tests came in. He did suggest that it was probably best if she rested for a while.

I was the last one to get up to leave; once the others had left the room, Dana asked me to stay.

“Nick,” she said, “tell me the truth. I want to know what’s going on. Why did I have a seizure?”

“There are lots of possible causes,” I said. “I wouldn’t worry too much.”

“Like what?”

She searched my face, trusting me, wanting to know. My sister knew that I would always tell her the truth.

“Anything, really. A sudden allergy. Stress. Maybe you’re epileptic, but the seizures hadn’t been triggered until now. Brain tumor. Maybe you ate something bad. Dehydration. Something just made your body go haywire for a little while. Lots of people have seizures. Seizures are actually quite common.”

She looked at me, zeroing in on the one cause I’d hoped she would overlook.

“Brain tumor?” she asked quietly.

I shrugged. “It can cause seizures, but believe me—it’s not all that likely that you have one. I’d say it’s the least likely of everything I mentioned.”

She glanced toward her lap. “I don’t want a brain tumor,” she said.

“Don’t worry,” I reassured her, hoping to hide my fears. “Like I said, that�

��s probably not the reason.”

Over the next few weeks, Dana underwent a number of tests. The doctors couldn’t find what was wrong with her. CAT scans were inconclusive, but since she had no more seizures, it seemed to us that the worst had passed. Still, the uncertainty weighed heavily on us; we still had no idea what had caused the seizure in the first place.

It had also come time for me to move to North Carolina.

Cat and I had talked about it numerous times since Dana had gone to the hospital; she suggested that we might consider staying, even though I’d have to find another job. Dana might need us, she said. We can put our dreams on hold for a while. At least until we know what’s going on.

It was one of those choices in life without any ideal option.

“Let me talk to Micah,” I finally said. “Let me see what he thinks.”

That night, when I explained the guilt I felt about moving away, he put his hand on my shoulder.

“There’s nothing you can do for Dana,” he said. “We don’t even know what’s wrong yet. But you’ve got to think about your family. You have a baby now. You’ve got to do what you think is best for him.”

I couldn’t meet his eyes.

“I don’t know . . .”

“I’ll watch out for Dana. I’m still here, and so is dad. And you’re only a flight away if we need you.”

“It doesn’t feel right to just leave, though.”

“I don’t want you to go either,” he said. Then, with a smile, he added, “But remember, Nick—what you want and what you get are usually two entirely different things.”

A few days before Christmas 1992, Cathy flew out with the baby to North Carolina to meet the moving van; I stayed behind to finish showing my brother around his new territory and introduce him to various doctors. Because our apartment had been emptied, I slept in my old room at my dad’s house the night before my departure.

Micah came over to help me pack my remaining items in the car: I would drive it cross-country. I noticed that he was wearing a pair of shorts of mine; because we were the same size, we had borrowed each other’s clothes for years.

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

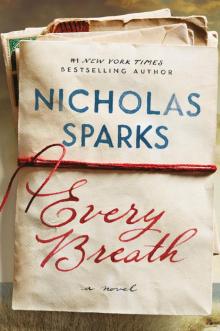

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath