- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

The Return Page 2

The Return Read online

Page 2

“Do you live here?” I heard a voice ask.

Glancing up, I saw the girl. She’d doubled back and was standing a few yards away, clearly keeping her distance, but close enough for me to notice a spray of light freckles on cheeks that were so pale as to seem almost translucent. On her arms I noted a couple of bruises, like she’d bumped into something. She wasn’t particularly pretty and there was something unfinished about her, which made me think again that she was a teenager. Her wary gaze suggested that she was prepared to run if I made the smallest move toward her.

“I do now,” I said, offering a smile. “But I don’t know how long I’ll be staying.”

“The old man died. The one who used to live here. His name was Carl.”

“I know. He was my grandfather.”

“Oh.” She slipped a hand into her back pocket. “He gave me honey.”

“That sounds like something he’d do.” I wasn’t sure if that was true, but it struck me as the right thing to say.

“He used to eat at the Trading Post,” she said. “He was always nice.”

Slow Jim’s Trading Post was one of those ramshackle stores so ubiquitous in the South and had been around longer than I’d been alive. My grandfather used to bring me there whenever I visited. It was the size of a three-car garage with a covered porch out front, and it sold everything from gas to milk and eggs, to fishing equipment, live bait, and auto parts. There were old-fashioned gas pumps out front—no credit or debit accepted—and a grill that served hot food. Once, I remember finding a bag of plastic toy soldiers wedged between a bag of marshmallows and a box of fishing hooks. There was little rhyme or reason to the offerings on the shelves or displayed on the walls, but I always thought it was one of the coolest stores ever.

“Do you work there?”

She nodded before pointing at the box in my hand. “Why are you putting mothballs around the house?”

I stared at the box in my hand, realizing that I’d forgotten I was holding it.

“There was a snake on my porch this morning. I’ve heard that mothballs will keep them away.”

She pursed her lips before taking a step backward. “Okay, then. I just wanted to know if you were living here now.”

“I’m Trevor Benson, by the way.”

At the sound of my name, she stared at me. Working up the courage to ask the obvious.

“What happened to your face?”

I knew she was referring to the thin scar that ran from my hairline to my jaw, which reinforced the impression of her youth. Adults usually wouldn’t bring it up. Instead, they’d pretend they hadn’t noticed. “Mortar round in Afghanistan. A few years back.”

“Oh.” She rubbed her nose with the back of her hand. “Did it hurt?”

“Yes.”

“Oh,” she said again. “I guess I’ll get going now.”

“All right,” I said.

She started back toward the road before suddenly turning around again. “It won’t work,” she called out.

“What won’t work?”

“The mothballs. Snakes don’t give a lick about mothballs.”

“You know that for sure?”

“Everyone knows it.”

Tell that to my grandfather, I thought. “Then what should I do? If I don’t want snakes on my porch?”

She seemed to consider her answer. “Maybe you should live in a place where there aren’t any snakes.”

I laughed. She was an odd one, for sure, but I realized that it was the first time I’d laughed since I’d moved here, maybe my first laugh in months.

“Nice meeting you.”

I watched her go, surprised when she slowly pirouetted. “I’m Callie,” she called out.

“Nice to meet you, Callie.”

When she finally vanished from view, blocked by the azaleas, I debated whether to continue putting out mothballs. I had no idea whether she was right or wrong, but in the end, I chose to call it a day. I was in the mood for some lemonade and wanted to sit on the back porch and relax, if only because my psychiatrist recommended that I take time to relax while I still had time.

He said it would help me keep The Darkness away.

* * *

My psychiatrist sometimes used flowery language like The Darkness to describe PTSD, also known as post-traumatic stress disorder. When I asked him why, he explained that every patient was different and that part of his job was to find words that accurately reflected the mood and feelings of the patient in a way that would lead the patient along the slow path toward recovery. Since he’d been working with me, he’d referred to my PTSD as turmoil, issues, struggle, the butterfly effect, emotion dysregulation, trigger sensitivity, and of course, The Darkness. It kept our sessions interesting, and I had to admit that darkness was about as accurate a description of the way I’d been feeling as any of them. For a long time after the explosion, my mood was dark, as black as the night sky without stars or a moon, even if I didn’t fully realize why. Early on, I was stubbornly in denial about PTSD, but then again, I’d always been stubborn.

In all candor, my anger, depression, and insomnia made perfect sense to me at the time. Whenever I glanced in the mirror, I was reminded of what had happened at Kandahar Airfield on September 9, 2011, when a rocket aimed at the hospital where I was working impacted near the entrance, only seconds after I’d exited the building. There is a bit of irony in my choice of words, since glancing in the mirror isn’t the same as it once was. I was blinded in my right eye, which means I have no depth perception. Staring at a reflection of myself feels a little like watching swimming fish on an old computer screen saver—almost real, but not quite—and even if I were able to get past that, my other wounds are as obvious as a lone flag planted atop Mount Everest. I’ve already mentioned the scar on my face, but shrapnel left my torso pockmarked like the moon. The pinkie and ring finger on my left hand were blown off—particularly unfortunate since I’m a lefty—and I lost my left ear as well. Believe it or not, that was the wound that bothered me the most about my appearance. A human head doesn’t look natural without an ear. I looked strangely lopsided and it wasn’t until that moment that I’d ever really appreciated my ear at all. In the rare times I thought about my ears, it was always in the context of hearing things. But try wearing sunglasses with just one ear and you’ll understand why I felt the loss acutely.

I haven’t yet mentioned the spinal injuries, which meant having to learn how to walk again, or the thrumming headaches that lingered for months, all of which left me a physical wreck. But the good doctors at Walter Reed fixed me up. Well, most of me, anyway. As soon as I was upright again, my care shifted to my old alma mater Johns Hopkins, where the cosmetic surgeries were performed. I now have a prosthetic ear—so well done I can hardly tell it’s fake—and my eye appears normal, even if it’s completely useless. They couldn’t do much about the fingers—they were fertilizer in Afghanistan by then—but a plastic surgeon was able to diminish the size of my facial scar to the thin, white line that it now is. It’s noticeable, but it’s not as though little kids scream at the sight of me. I like to tell myself that it adds character, that beneath the surface of the suave and debonair man before you exists a man of intensity and courage, who has experienced and survived real danger. Or something like that.

Still, along with my body, my entire life was blown up as well, including my career. I didn’t know what to do with myself or my future; I didn’t know how to handle the flashbacks or insomnia or my hair-trigger anger, or any of the other crazy symptoms associated with PTSD. Things went from bad to worse until I hit rock bottom—think a four-day bender, where I woke covered in vomit—and I finally realized that I needed help. I found a psychiatrist named Eric Bowen, who was an expert in CBT and DBT, or cognitive and dialectical behavioral therapies. In essence, both CBT and DBT focus on behaviors as a way to help control or manage what you’re thinking or feeling. If you’re feeling put-upon, force yourself to stand up straight; if you’re feeling overwhelm

ed because you’re faced with a complex task, try to lessen that sensation with simple tasks of things you can do, like starting with the first easy step, and then, after that, doing the next simple thing.

It takes a lot of work to modify behavior—and there are a lot of other aspects to CBT and DBT—but slowly but surely I started to get my act back together. With that came thoughts of the future. Dr. Bowen and I discussed all sorts of career options, but in the end, I realized that I missed the practice of medicine. I contacted Johns Hopkins and applied for another residency. This time, in psychiatry. I think Bowen was flattered by that. Long story short, strings were pulled—maybe because I’d been there before, maybe because I was a disabled vet—and exceptions were granted. I was accepted as a psychiatric resident, with a start date in July. Not long after I’d received the congratulatory notification from Johns Hopkins, I learned that my grandfather had had a stroke. It occurred in Easley, South Carolina, a town I’d never heard him mention before. I was urged to come to the hospital quickly, as he didn’t have much time left.

I couldn’t fathom why he was there. As far as I knew, he hadn’t left New Bern in years. By the time I got there and found him in the hospital, he could barely speak; it was all he could do to choke out a single word at a time. Even those were hard to understand. He said some odd things to me, things that hurt me even if they made no sense, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that he was trying to communicate something important before he finally passed away.

As his only remaining family, it was up to me to make the funeral arrangements. I was certain he wanted to be buried in New Bern. I had him transported back to his hometown, set up a small graveside service, which had more attendees than I’d imagined there would be, and spent a lot of time at his house, wandering the property and wrestling with my grief and guilt. Because my parents were so busy with their own lives, I’d spent most of my summers growing up in New Bern, and I missed my grandfather with an ache that felt like a physical vise. He was funny, he was wise and kind, and he always made me feel older and smarter than I really was. When I was eight, he let me take a puff from his corncob pipe; he taught me how to fly-fish and let me help whenever he repaired an engine. He taught me everything about bees and beekeeping, and when I was a teenager, he told me that one day, I would meet a woman who would change my life forever. When I asked how I would know if I’d met the right one, he winked and told me that if I wasn’t sure, then I’d better just keep on looking.

Somehow, with all that had happened since Kandahar, I hadn’t made time to visit him during the past few years. I know he worried about my condition, but I hadn’t wanted to share with him the demons I was battling. Hell, it was hard enough to talk about my life with Dr. Bowen, and even though I knew my grandfather wouldn’t judge me, it felt easier to keep my distance. It crushed me that he was taken before I had the chance to really reconnect with him. To top it off, a local attorney contacted me right after the funeral to let me know that I’d inherited my grandfather’s property, so I found myself the owner of the very home where I’d spent so many formative summers as a kid. In the weeks following the funeral, I spent a lot of time reflecting on all the words I’d left unspoken to the man who had loved me so unconditionally.

My mind also kept returning to the odd things my grandfather had said to me on his deathbed, and I wondered why he’d been in Easley, South Carolina, in the first place. Did it have something to do with the bees? Was he visiting an old friend? Dating a woman? The questions continued to gnaw at me. I spoke to Dr. Bowen about it, and he suggested that I try to find the answers. The holidays passed without notice, and with the arrival of the new year I listed my condo with a realtor, thinking it might take a few months to sell. Lo and behold, I had an offer within days, and closed in February. Since I’d soon be moving to Baltimore for residency, it didn’t make sense to find a place to rent temporarily. I thought about my grandfather’s place in New Bern and figured, why not?

I could get out of Pensacola, maybe get the old place ready to sell. If I was lucky, I might even be able to figure out why my grandfather had been in Easley, and what on earth he’d been trying to tell me.

Which is how and why I found myself scattering mothballs outside his rattletrap old cabin.

* * *

I didn’t really have lemonade on the back porch. That’s how my grandfather used to refer to beer, and when I was little, one of the great thrills of my young life was getting him a lemonade from the icebox. Strangely, it always came in a bottle labeled Budweiser.

I prefer Yuengling, from America’s oldest brewery. When I attended the Naval Academy, an upperclassman named Ray Kowalski introduced me to it. He was from Pottsville, Pennsylvania—home of the Yuengling Brewery—and he convinced me there was no finer beer. Interestingly, Ray was also the son of a coal miner and last I heard, he was serving on the USS Hawaii, a nuclear submarine. I guess he learned from his dad that when you’re working, sunlight and fresh air are overrated.

I wonder what my mom and dad would have thought about my life these days. After all, I haven’t worked in more than two years. I’m pretty sure my dad would have been appalled; he was the kind of father who would sit me down for a lecture if I received an A− on an exam and was disappointed when I chose the Naval Academy over Georgetown, his alma mater, or Yale, where he’d received his law degree. He woke at five in the morning every day of the week, read both the Washington Post and the New York Times while having his coffee, then would head to DC, where he worked as a lobbyist for whatever company or industry group had hired him. A sharp mind and an aggressive negotiator, he lived to make a deal and could quote large sections of the tax code from memory. He was one of six partners who oversaw more than two hundred attorneys, and his walls were decorated with photographs of him with three different presidents, half a dozen senators, and too many congressmen to count.

My dad didn’t simply work; his hobby was work. He spent seventy hours a week at the office and golfed with clients and politicians on the weekends. Once a month, he hosted a cocktail party at our home, with still more clients and politicians. In the evenings, he often secluded himself in his office, where there was always a pressing phone call to make, a brief to be written, a plan to be made. The idea of him kicking back on the porch and having a beer in the middle of the afternoon on a workday would have struck him as absurd, something a slacker might do, but never a Benson. There was nothing worse than being a slacker, in my father’s eyes.

Though he wasn’t the nurturing type, he wasn’t a bad father. To be fair, my mother wasn’t exactly a cookie-baking, hands-on PTA member, either. A neurosurgeon trained at Johns Hopkins, she was frequently on call and was a good match for my father in her drive and passion for work. My grandfather always said she came out of the wrapper that way, belying her small-town background and the fact that neither of her parents went to college. But I never doubted her or my father’s love for me, even if we ate takeout for dinner every night and I attended more cocktail parties as a teenager than family camping trips.

In any case, my family was hardly unusual for Alexandria. Everyone at my elite private school had high-powered and prosperous parents, and the culture of excellence and career success filtered down to their children. Stellar grades were the norm, but even that wasn’t enough. Kids were also expected to excel at sports or music or both and be popular to boot. I’ll admit I got sucked into all of it; by the time I was in high school, I felt the need to be…just like them. I dated popular girls, finished second in my class, made all-state soccer in my junior and senior years, and was proficient on the piano. At the Naval Academy, I started on the soccer team all four years, double majored in chemistry and mathematics, and did well enough on my MCATs to be accepted to Johns Hopkins for medical school, making my mother proud.

Sadly, my parents weren’t around to watch me receive my diploma. The accident was something I don’t like to think about, nor do I like to tell others what happened. Most people don’t know what

to say, conversation falters, and I’m usually left feeling even worse than had I said nothing about them at all.

Then again, I sometimes wondered whether I just hadn’t told the story to the right person, or if that person was even out there. Someone should be able to empathize, right? What I can say, however, is that I’ve come to accept that life never turns out quite like one expects.

Chapter 2

I know what you might be thinking: How can a guy who considered himself a mental and emotional basket case for the last two and a half years even think about becoming a psychiatrist? How can I help anyone if I’ve barely figured out my own life?

Good questions. As for the answers…hell, I didn’t know. Maybe I’d never be able to help anyone. What I did know was that my options were somewhat limited. Anything surgical was out—what with the partial blindness and missing fingers and all—and I wasn’t interested in either family practice or internal medicine.

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

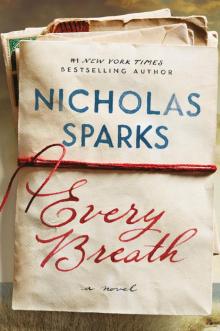

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath