- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

A Bend in the Road Page 2

A Bend in the Road Read online

Page 2

As the summer wore on, the thoughts about finding someone new began to surface more frequently and with more intensity. Missy was still there, Missy would always be there ... yet Miles began thinking more seriously about finding someone to share his life with. Late at night, while comforting Jonah in the rocking chair out back—it was the only thing that seemed to help with the nightmares—these thoughts seemed strongest and always followed the same pattern. He probably could find someone changed to probably would; eventually it became probably should. At this point, however—no matter how much he wanted it to be otherwise—his thoughts still reverted back to probably won’t.

The reason was in his bedroom.

On his shelf, in a bulging manila envelope, sat the file concerning Missy’s death, the one he’d made for himself in the months following her funeral. He kept it with him so he wouldn’t forget what happened, he kept it to remind him of the work he still had to do.

He kept it to remind him of his failure.

A few minutes later, after stubbing out the cigarette on the railing and heading inside, Miles poured the coffee he needed and headed down the hall. Jonah was still asleep when he pushed open the door and peeked in. Good, he still had a little time. He headed to the bathroom.

After he turned the faucet, the shower groaned and hissed for a moment before the water finally came. He showered and shaved and brushed his teeth. He ran a comb through his hair, noticing again that there seemed to be less of it now than there used to be. He hurriedly donned his sheriff’s uniform; next he took down his holster from the lockbox above the bedroom door and put that on as well. From the hallway, he heard Jonah rustling in his room. This time, Jonah looked up with puffy eyes as soon as Miles came in to check on him. He was still sitting in bed, his hair disheveled. He hadn’t been awake for more than a few minutes.

Miles smiled. “Good morning, champ.”

Jonah looked up from his bed, almost as if in slow motion. “Hey, Dad.”

“You ready for some breakfast?”

He stretched his arms out to the side, groaning slightly. “Can I have pancakes?”

“How about some waffles instead? We’re running a little late.”

Jonah bent over and grabbed his pants. Miles had laid them out the night before. “You say that every morning.”

Miles shrugged. “You’re late every morning.”

“Then wake me up sooner.”

“I have a better idea—why don’t you go to sleep when I tell you to?”

“I’m not tired then. I’m only tired in the mornings.”

“Join the club.”

“Huh?”

“Never mind,” Miles answered. He pointed to the bathroom. “Don’t forget to brush your hair after you get dressed.”

“I won’t,” Jonah said.

Most mornings followed the same routine. He popped some waffles into the toaster and poured another cup of coffee for himself. By the time Jonah had dressed himself and made it to the kitchen, his waffle was waiting on his plate, a glass of milk beside it. Miles had already spread the butter, but Jonah liked to add the syrup himself. Miles started in on his own waffle, and for a minute, neither of them said anything. Jonah still looked as if he were in his own little world, and though Miles needed to talk to him, he wanted him to at least seem coherent.

After a few minutes of companionable silence, Miles finally cleared his throat.

“So, how’s school going?” he asked.

Jonah shrugged. “Fine, I guess.”

This question too, was part of the routine. Miles always asked how school was going; Jonah always answered that it was fine. But earlier that morning, while getting Jonah’s backpack ready, Miles had found a note from Jonah’s teacher, asking him if it was possible to meet today. Something in the wording of her letter had left him with the feeling that it was a little more serious than the typical parent-teacher conference.

“You doing okay in class?”

Jonah shrugged. “Uh-huh.”

“Do you like your teacher?”

Jonah nodded in between bites. “Uh-huh,” he answered again.

Miles waited to see if Jonah would add anything more, but he didn’t. Miles leaned a little closer.

“Then why didn’t you tell me about the note your teacher sent home?”

“What note?” he asked innocently.

“The note in your backpack—the one your teacher wanted me to read.”

Jonah shrugged again, his shoulders popping up and down like the waffles in the toaster. “I guess I just forgot.”

“How could you forget something like that?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you know why she wants to see me?”

“No . . .” Jonah hesitated, and Miles knew immediately that he wasn’t telling the truth.

“Son, are you in trouble at school?”

At this, Jonah blinked and looked up. His father didn’t call him “son” unless he’d done something wrong. “No, Dad. I don’t ever act up. I promise.”

“Then what is it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Think about it.”

Jonah squirmed in his seat, knowing he’d reached the limit of his father’s patience. “Well, I guess I might be having a little trouble with some of the work.”

“I thought you said school was going okay.”

“School is going okay. Miss Andrews is really nice and all, and I like it there.” He paused. “It’s just that sometimes I don’t understand everything that’s going on in class.”

“That’s why you go to school. So you can learn.”

“I know,” he answered, “but she’s not like Mrs. Hayes was last year. The work she assigns is hard. I just can’t do some of it.”

Jonah looked scared and embarrassed at exactly the same time. Miles reached out and put his hand on his son’s shoulder.

“Why didn’t you tell me you were having trouble?”

It took a long time for Jonah to answer.

“Because,” he said finally, “I didn’t want you to be mad at me.”

After breakfast, after making sure Jonah was ready to go, Miles helped him with his backpack and led him to the front door. Jonah hadn’t said much since breakfast. Squatting down, Miles kissed him on the cheek. “Don’t worry about this afternoon. It’s gonna be all right, okay?”

“Okay,” Jonah mumbled.

“And don’t forget that I’ll be picking you up, so don’t get on the bus.”

“Okay,” he said again.

“I love you, champ.”

“I love you, too, Dad.”

Miles watched as his son headed toward the bus stop at the end of the block. Missy, he knew, wouldn’t have been surprised by what had happened this morning, as he had been. Missy would have already known that Jonah was having trouble at school. Missy had taken care of things like this.

Missy had taken care of everything.

Chapter 2

The night before she was to meet with Miles Ryan, Sarah Andrews was walking through the historic district in New Bern, doing her best to keep a steady pace. Though she wanted to get the most from her workout—she’d been an avid walker for the past five years—since she’d moved here, she’d found it hard to do. Every time she went out, she found something new to interest her, something that would make her stop and stare.

New Bern, founded in 1710, was situated on the banks of the Neuse and Trent Rivers in eastern North Carolina. As the second oldest town in the state, it had once served as the capital and been home to the Tryon Palace, residence of the colonial governor. Destroyed by fire in 1798, the palace had been restored in 1954, complete with some of the most breathtaking and exquisite gardens in the South. Throughout the grounds, tulips and aza-leas bloomed each spring, and chrysanthemums blossomed in the fall. Sarah had taken a tour when she’d first arrived. Though the gardens were between seasons, she’d nonetheless left the palace wanting to live within walking distance so she could pass its gates each day.

She’d moved into a quaint apartment on Middle Street a few blocks away, in the heart of downtown. The apartment was up the stairs and three doors away from the pharmacy where in 1898 Caleb Bradham had first marketed Brad’s drink, which the world came to know as Pepsi-Cola. Around the corner was the Episco-pal church, a stately brick structure shaded with towering magnolias, whose doors first opened in 1718. When she left her apartment to take her walk, Sarah passed both sites as she made her way to Front Street, where many of the old mansions had stood gracefully for the past two hundred years.

What she really admired, however, was the fact that most of the homes had been painstakingly restored over the past fifty years, one house at a time. Unlike Williamsburg, Virginia, which was restored largely through a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, New Bern had appealed to its citizens and they had responded. The sense of community had lured her parents here four years earlier; she’d known nothing about New Bern until she’d moved to town last June.

As she walked, she reflected on how different New Bern was from Baltimore, Maryland, where she’d been born and raised, where she’d lived until just a few months earlier. Though Baltimore had its own rich history, it was a city first and foremost. New Bern, on the other hand, was a small southern town, relatively isolated and largely uninterested in keeping up with the ever quickening pace of life elsewhere. Here, people would wave as she passed them on the street, and any question she asked usually solicited a long, slow-paced answer, generally peppered with references to people or events that she’d never heard of before, as if everything and everyone were somehow connected. Usually it was nice, other times it drove her batty.

Her parents had moved here after her father had taken a job as hospital administrator at Craven

Regional Medical Center. Once Sarah’s divorce had been finalized, they’d begun to prod her to move down as well. Knowing how her mother was, she’d put it off for a year. Not that Sarah didn’t love her mother, it was just that her mother could sometimes be... draining, for lack of a better word. Still, for peace of mind she’d finally taken their advice, and so far, thankfully, she hadn’t regretted it. It was exactly what she needed, but as charming as this town was, there was no way she saw herself living here forever.

New Bern, she’d learned almost right away, was not a town for singles. There weren’t many places to meet people, and the ones her own age that she had met were already married, with families of their own. As in many southern towns, there was still a social order that defined town life. With most people married, it was hard for a single woman to find a place to fit in, or even to start. Especially someone who was divorced and completely new to the area.

It was, however, an ideal place to raise children, and sometimes as she walked, Sarah liked to imagine that things had turned out differently for her. As a young girl, she’d always assumed she would have the kind of life she wanted: marriage, children, a home in a neighborhood where families gathered in the yards on Friday evenings after work was finished for the week. That was the kind of life she’d had as a child, and it was the kind she wanted as an adult. But it hadn’t worked out that way. Things in life seldom did, she’d come to understand.

For a while, though, she had believed anything was possible, especially when she’d met Michael. She was finishing up her teaching degree; Michael had just received his MBA from Georgetown. His family, one of the most prominent in Baltimore, had made their fortune in banking and were immensely wealthy and clannish, the type of family that sat on the boards of various corporations and instituted policies at country clubs that served to exclude those they regarded as inferior. Michael, however, seemed to reject his family’s values and was regarded as the ultimate catch. Heads would turn when he entered a room, and though he knew what was happening, his most endearing quality was that he pretended other people’s images of him didn’t matter at all.

Pretended, of course, was the key word.

Sarah, like every one of her friends, knew who he was when he showed up at a party, and she’d been surprised when he’d come up to say hello a little later in the evening. They’d hit it off right away. The short conversation had led to a longer one over coffee the following day, then eventually to dinner. Soon they were dating steadily and she’d fallen in love. After a year, Michael asked her to marry him.

Her mother was thrilled at the news, but her father didn’t say much at all, other than that he hoped that she would be happy. Maybe he suspected something, maybe he’d simply been around long enough to know that fairy tales seldom came true. Whatever it was, he didn’t tell her at the time, and to be honest, Sarah didn’t take the time to question his reservations, except when Michael asked her to sign a prenuptial agreement. Michael explained that his family had insisted on it, but even though he did his best to cast all the blame on his parents, a part of her suspected that had they not been around, he would have insisted upon it himself. She nonetheless signed the papers. That evening, Michael’s parents threw a lavish engagement party to formally announce the upcoming marriage.

Seven months later, Sarah and Michael were married. They honeymooned in Greece and Turkey; when they got back to Baltimore, they moved into a home less than two blocks from where Michael’s parents lived. Though she didn’t have to work, Sarah began teaching second grade at an inner-city elementary school. Surprisingly, Michael had been fully supportive of her decision, but that was typical of their relationship then. In the first two years of their marriage, everything seemed perfect: She and Michael spent hours in bed on the weekends, talking and making love, and he confided in her his dreams of entering politics one day. They had a large circle of friends, mainly people Michael had known his entire life, and there was always a party to attend or weekend trips out of town. They spent their remaining free time in Washington, D.C., exploring museums, attending the theater, and walking among the monuments located at the Capitol Mall. It was there, while standing inside the Lincoln Memorial, that Michael told Sarah he was ready to start a family. She threw her arms around him as soon as he’d said the words, knowing that nothing he could have said would have made her any happier.

Who can explain what happened next? Several months after that blissful day at the Lincoln Memorial, Sarah still wasn’t pregnant. Her doctor told her not to worry, that it sometimes took a while after going off the pill, but he suggested she see him again later that year if they were still having problems.

They were, and tests were scheduled. A few days later, when the results were in, they met with the doctor. As they sat across from him, one look was enough to let her know that something was wrong.

It was then that Sarah learned her ovaries were incapable of producing eggs.

A week later, Sarah and Michael had their first major fight. Michael hadn’t come home from work, and she’d paced the floor for hours while waiting for him, wondering why he hadn’t called and imagining that something terrible had happened. By the time he came home, she was frantic and Michael was drunk. “You don’t own me” was all he offered by way of explanation, and from there, the argument went downhill fast. They said terrible things in the heart of the moment. Sarah regretted all of them later that night; Michael was apologetic. But after that, Michael seemed more distant, more reserved. When she pressed him, he denied that he felt any differently toward her. “It’ll be okay,” he said, “we’ll get through this.”

Instead, things between them grew steadily worse. With every passing month, the arguments became more frequent, the distance more pronounced. One night, when she suggested again that they could always adopt, Michael simply waved off the suggestion: “My parents won’t accept that.”

Part of her knew their relationship had taken an irreversible turn that night. It wasn’t his words that gave it away, nor was it the fact that he seemed to be taking his parents’ side. It was the look on his face—the one that let her know he suddenly seemed to regard the problem as hers, not theirs.

Less than a week later, she found Michael sitting in the dining room, a glass of bourbon at his side. From the unfocused look in his eyes, she knew it wasn’t the first one he’d had. He wanted a divorce, he began; he was sure she understood. By the time he was finished, Sarah found herself unable to say anything in response, nor did she want to.

The marriage was over. It had lasted less than three years. Sarah was twenty-seven years old.

The next twelve months were a blur. Everyone wanted to know what had gone wrong; other than her family, Sarah told no one. “It just didn’t work out” was all she would say whenever someone asked.

Because she didn’t know what else to do, Sarah continued to teach. She also spent two hours a week talking to a wonderful counselor, Sylvia. When Sylvia recommended a support group, Sarah went to a few of the meetings. Mostly, she listened, and she thought she was doing better. But sometimes, as she sat alone in her small apartment, the reality of the situation would bear down hard and she would begin to cry again, not stopping for hours. During one of her darkest periods, she’d even considered suicide, though no one—not the counselor, not her family—knew that. It was then that she’d realized she had to leave Baltimore; she needed a place to start over. She needed a place where the memories wouldn’t be so painful, somewhere she’d never lived before.

Now, walking the streets of New Bern, Sarah was doing her best to move on. It was still a struggle at times, but not nearly as bad as it once had been. Her parents were supportive in their own way—her father said nothing whatsoever about it; her mother clipped out magazine articles that touted the latest medical developments—but her brother, Brian, before he headed off for his first year at the University of North Carolina, had been a lifesaver.

Like most adolescents, he was sometimes distant and withdrawn, but he was a truly empathetic listener. Whenever she’d needed to talk, he’d been there for her, and she missed him now that he was gone. They’d always been close; as his older sister, she’d helped to change his diapers and had fed him whenever her mother let her. Later, when he was going to school, she’d helped him with his homework, and it was while working with him that she’d realized she wanted to become a teacher.

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

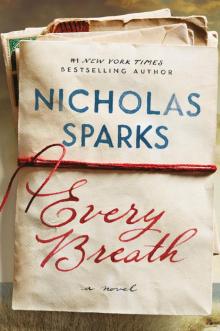

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath