- Home

- Nicholas Sparks

Three Weeks With My Brother Page 2

Three Weeks With My Brother Read online

Page 2

“I’m sure it will be, little brother.” I could almost see Micah grinning on the other end. “It will be.”

We said our good-byes, and after hanging up the phone I found myself eyeing the family photographs that line the shelves of my office. For the most part, the pictures are of the kids: I saw my children as infants and as toddlers; there was a Christmas photograph of all five of them, taken only a couple of months earlier. Beside that stood a photograph of Cathy, and on impulse I reached for the frame, thinking of the sacrifice she’d just made.

No, she wasn’t thrilled with the idea of me leaving for three weeks. Nor was she thrilled that I wouldn’t be around to help with our five children; instead, she’d shoulder the load while I traveled the world.

Why then, had she said yes?

As I’ve said, my wife understands me better than anyone, and knew my urgent desire to go had less to do with the trip itself than spending time with my brother.

This, then, is a story about brotherhood.

It’s the story of Micah and me, and the story of our family. It’s a story of tragedy and joy, hope and support. It’s the story of how he and I have matured and changed and taken different paths in life, but somehow grown even closer. It is, in other words, the story of two journeys; one journey that took my brother and me to exotic places around the world, and another, a lifetime in the making, that has led us to become the best of friends.

CHAPTER 1

Many stories begin with a simple lesson learned, and our family’s story is no exception. For brevity’s sake, I’ll summarize.

In the beginning, we children were conceived. And the lesson learned—at least according to my Catholic mother—goes like this:

“Always remember,” she told me, “that no matter what the church tells you, the rhythm method doesn’t work.”

I looked up at her, twelve years old at the time. “You mean to say that we were all accidents?”

“Yep. Each and every one of you.”

“But good accidents, right?”

She smiled. “The very best kind.”

Still, after hearing this story, I wasn’t sure quite what to think. On one hand, it was obvious that my mom didn’t regret having us. On the other hand, it wasn’t good for my ego to think of myself as an accident, or to wonder whether my sudden appearance in the world came about because of one too many glasses of champagne. Still, it did serve to clear things up for me, for I’d always wondered why our parents hadn’t waited before having children. They certainly weren’t ready for us, but then, I’m not exactly sure they’d been ready for marriage either.

Both my parents were born in 1942, and with World War II in its early stages, both my grandfathers served in the military. My paternal grandfather was a career officer; my dad, Patrick Michael Sparks, spent his childhood moving from one military base to the next, and growing up largely in the care of his mother. He was the oldest of five siblings, highly intelligent, and attended boarding school in England before his acceptance at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska. It was there that he met my mom, Jill Emma Marie Thoene.

Like my dad, my mom was the oldest child in her family. She had three younger brothers and sisters, and was mostly raised in Nebraska where she developed a lifelong love of horses. Her father was an entrepreneur who ran a number of different businesses in the course of his life. When my mom was a teenager, he owned a movie theater in Lyons, a tiny town of a few hundred people nestled just off the highway in the midst of farmland. According to my mom, the theater was part of the reason she’d attended boarding school as well. Supposedly, she’d been sent away because she’d been caught kissing a boy, though when I asked about it, my grandmother adamantly denied it. “Your mother always was a storyteller,” my grandmother informed me. “She used to make up the darnedest things, just to get a reaction from you kids.”

“So why did you ship her off to boarding school?”

“Because of all the murders,” my grandmother said. “Lots of young girls were getting killed in Lyons back then.”

I see.

Anyway, after boarding school, my mother headed off to Creighton University just like my dad, and I suppose it was the similarities between my parents’ lives that first sparked their interest in each other. Whatever the reason, they began dating as sophomores, and gradually fell in love. They courted for a little more than a year, and were both twenty-one when they married on August 31, 1963, prior to the beginning of their senior year in college.

A few months later, the rhythm method failed and my mom learned the first of her three lessons. Micah was born on December 1, 1964. By spring, she was pregnant again, and I followed on December 31, 1965. By the following spring, she was pregnant with my sister, Dana, and decided that from that point on, she would take birth control matters into her own hands.

After graduation, my dad chose to pursue a master’s degree in business at the University of Minnesota and the family moved near Watertown in the autumn of 1966. My sister, Dana, was born, like me, on December 31, and my mother stayed home to raise us while my father went to school during the day and tended bar at night.

Because my parents couldn’t afford much in the way of rent, we lived miles from town in an old farmhouse that my mother swore was haunted. Years later, she told me that she used to see and hear things late at night—crying, laughing, and whispered conversations—but as soon as she would get up to check on us, the noises would fade away.

A likelier explanation was that she was hallucinating. Not because she was crazy—my mom was probably the most stable person I’ve ever known—but because she must have spent those first few years in a foggy world of utter exhaustion. And I don’t mean the kind of exhaustion easily remedied by a couple of days of sleeping in late. I mean the kind of unending physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion that makes a person look like they’ve been swirled around in circles by their earlobes for hours before being plunked down at the kitchen table in front of you. Her life must have been absolute hell. Beginning at age twenty-five, with three babies in cloth diapers—with the exception of those times when her mother came to visit—she was completely isolated for the next two years. There was no family nearby to lend support, we were poor as dirt, and we lived in the middle of nowhere. Nor could my mom so much as venture into the nearest town, for my father took the car with him to both school and work. Throw in a couple of Minnesota winters where snow literally reached the roof, subtract my always busy dad from the equation, throw in the unending whining and crying of babies and toddlers, and even then I’m not sure it’s possible to imagine how miserable she must have been. Nor was my father much help—at that point in his life, he simply couldn’t. I’ve often wondered why he didn’t get a regular job, but he didn’t, and it was all he could do to work and study and attend his classes. He would leave first thing in the morning and return long after everyone else had gone to bed. So with the exception of three little kids, my mother had absolutely no one to talk to. She must have gone days or even weeks without having a single adult conversation.

Because he was the oldest, my mom saddled Micah with responsibilities far beyond his years—certainly with more responsibility than I’d ever trust my kids with. My mom was notorious for drumming old-fashioned, midwestern values into our heads and my brother’s command soon became, “It’s your job to take care of your brother and sister, no matter what.” Even at three, he did. He helped feed me and my sister, bathed us, entertained us, watched us as we toddled around the yard. There are pictures in our family albums of Micah rocking my sister to sleep while feeding her a bottle, despite the fact that he wasn’t all that much bigger than she was. I’ve come to understand that it was good for him, because a person has to learn a sense of responsibility. It doesn’t magically appear one day, simply because you suddenly need it. But I think that because Micah was frequently treated as an adult, he actually believed he was an adult, and that certain rights were owed him. I suppose that’s what led to an almost

adult sense of stubborn entitlement long before he started school.

My earliest memory, in fact, is about my brother. I was two and a half—Micah a year older—on a late-summer weekend, and the grass was about a foot high. My dad was getting ready to mow the lawn and had pulled the lawn mower out from the shed. Now Micah loved the lawn mower, and I vaguely remember my brother pleading with my father to let him mow the lawn, despite the fact that he wasn’t even strong enough to push it. My dad said no, of course, but my brother—all thirty pounds of him—couldn’t see the logic of the situation. Nor, he told me later, was he going to put up with such nonsense.

In his own words, “I decided to run away.”

Now, I know what you’re thinking. He’s three and a half years old—how far could he go? My oldest son, Miles, used to threaten to run away at that age, too, and my wife and I responded thus: “Go ahead. Just make sure you don’t go any farther than the corner.” Miles, being the gentle and fearful child that he was, would indeed go no farther than the corner, where my wife and I would watch him from the kitchen window.

Not my brother. No, his thinking went like this: “I’m going to run far away, and since I’m always supposed to take care of my brother and sister, then I guess I have to take them with me.”

So he did. He loaded my eighteen-month-old sister in the wagon, took my hand, and sneaking behind the hedges so my parents couldn’t see us, began leading us to town. Town, by the way, was two miles away, and the only way to get there was to cross a busy two-lane highway.

We nearly made it, too. I remember marching through fields with weeds nearly as tall as I was, watching butterflies explode into the summer sky. We kept going for what seemed like forever before finally reaching the highway. There we stood on the shoulder of the road—three children under four, mind you, and one in diapers—buffeted by powerful gusts of wind as eighteen-wheelers and cars rushed past us at sixty miles an hour, no more than a couple of feet away. I remember my brother telling me, “You have to run fast when I tell you,” and the sounds of honking horns and screeching tires after he screamed “Run!” while I toddled across the road, trying to keep up with him.

After that, things are a little sketchy. I remember getting tired and hungry, and finally crawling into the wagon with my sister, while my brother dragged us along like Balto, the lead husky, pushing through Alaskan snow. But I also remember being proud of him. This was fun, this was an adventure. And despite everything, I felt safe. Micah would take care of me, and my command from my mother had always been, “Do what your brother tells you.”

Even then, I did as I was told. Unlike my brother, I would grow up doing what I was told.

Sometime later, I remember heading over a bridge and up a hill; once we reached the top, we could see the town in the valley below. Years later, I understood that we must have been gone for hours—little legs can only cover two miles so fast—and I vaguely remember my brother promising us some ice cream to eat. Just then, we heard shouting, and as I looked over my shoulder, I saw my mother, frantically rushing up the road behind us. She was screaming at us to STOP! while wildly waving a flyswatter over her head.

That’s what she used to punish us, by the way. The flyswatter.

My brother hated the flyswatter.

Micah was unquestionably the most frequent recipient of the flyswatter punishment. My mom liked it because even though it stung, it didn’t really hurt, and it made a loud noise when connecting with the diaper or through pants. The sound was what really got to you—it’s like the popping of a balloon—and to this day, I still feel a strange sort of retributive glee when I swat insects in my home.

It wasn’t long after the first time Micah ran away that he did it again. For whatever reason, he got in trouble, and this time it was my dad who went for the flyswatter. By then, Micah had grown tired of this particular punishment, so when he saw my father reaching for it, he said firmly, “You’re not going to swat me with it.”

My dad turned, flyswatter in hand, and that’s when Micah took off. Sitting in the living room, I watched as my four-year-old brother raced from the kitchen, flew by me, and headed up the stairs with my dad close behind. I heard the thumping upstairs as my brother performed various, unknown acrobatics in the bedroom, and a moment later, he was zipping back down the stairs, past me again, through the kitchen and blasting through the back door, moving faster than I’d ever seen him move.

My dad, huffing and puffing—he was a lifelong smoker—rumbled down the stairs, and followed him. I didn’t see either of them again for hours. After it was dark, when I was already in bed, I looked up to see my mom leading Micah into our room. My mom tucked him in bed and kissed him on the cheek. Despite the darkness, I could see he was filthy; smeared with dirt, he looked like he’d spent the past few hours underground. As soon as she left, I asked Micah what happened.

“I told him he wasn’t going to swat me,” he said.

“Did he?”

“No. He couldn’t catch me. Then he couldn’t find me.”

I smiled, thinking, I knew you’d make it.

CHAPTER 2

A couple of days after I sent Micah the information about the trip, the phone rang. I was at my desk in the office, struggling through another difficult day of writing, and when I picked up the receiver Micah began rattling on almost immediately.

“This trip is . . . amazing,” he said. “Have you seen where we’re going to be going? We’re going to Easter Island and Cambodia! We’re going to see the Taj Mahal! We’re going to the Australian outback!”

“I know,” I said, “doesn’t it sound great?”

“It’s more than great. It’s awesome! Did you see that we’re going on a dogsled ride in Norway?”

“Yeah, I know . . .”

“We’ll ride elephants in India!”

“I know . . .”

“We’re going to Africa! Africa, for God’s sake!”

“I know . . .”

“This is going to be great!”

“So Christine said you could go?”

“I told you I’m going.”

“I know. But is Christine okay with it?”

“She’s not exactly thrilled, but she okayed it. I mean . . . Africa! India! Cambodia! With my brother? What’s she going to say?”

She could have said no, I thought. They had two kids—Peyton was only a couple of months old, Alli was nine—and Micah was planning to leave for a month shortly after Peyton’s first birthday. But I was certain that Christine, like Cathy, understood that Micah needed to see me as much as I needed to see him, albeit for different reasons. As siblings, we’d come to depend on each other in times of crisis, a dependence that had grown only stronger as we aged. We’d supported each other through personal and emotional struggles, we’d lived each other’s ups and downs. We’d learned a lot about ourselves by learning about each other, and while siblings by nature often are close, with Micah and me, it went a step further. The sound of his voice never failed to remind me of the childhood we’d shared, and his laughter inevitably resurrected distant memories, long-lost images unfurling without warning, like flags on a breezy day.

“Nick? Hello? You still there?”

“Yeah, I’m here. Just thinking.”

“About what? The trip?”

“No,” I said. “I was thinking about the adventures we had when we were little kids.”

“In Minnesota?”

“No,” I said. “In Los Angeles.”

“What made you think of that?”

“I’m not exactly sure,” I admitted. “Sometimes it just happens.”

In 1969, we moved from the cold winters of Minnesota to Inglewood, California. My dad had been accepted into the doctoral program at the University of Southern California, and we moved to what some might consider the projects. Smack dab in the center of Los Angeles, the community where we lived still smoldered with the angry memories of the Watts riots in 1965. We were one of only a few white families in the run

-down apartment complex we called home, and our immediate neighbors included prostitutes, drug dealers, and gang members.

It was a tiny place—two bedrooms, living room, and a kitchen—but I’m sure my mom viewed it as a vast improvement over her life in Minnesota. Even though she still didn’t have the support of family, for the first time in two years she had neighbors to talk to, even if they were different from the folks she grew up with in Nebraska. It was also possible for her to walk to the store to buy groceries, or at least walk outside and see signs of human life.

It’s common for children to think of their parents reverentially, and as a child, I was no different. With dark brown eyes, dark hair, and milky skin, my mom seemed beautiful to me. Despite the harshness of our early life, I never remember her taking her frustrations out on us. She was one of those women who were born to be a mother, and she loved us unconditionally; in many ways, we were her life. She smiled more than anyone I’ve ever known. Hers weren’t those fake smiles, the kind that seem forced and give you the creeps. Hers were genuine smiles that made you want to run into her arms, which were always held open for us.

My dad, on the other hand, was still somewhat of a mystery to me. With sandy, reddish hair, he had freckles and was prone to sunburns. Among all of us, only he had an appreciation for music. He played the harmonica and the guitar, and he whistled compulsively when he was stressed, which he always seemed to be. Not that anyone could blame him. In Los Angeles, he settled into the same grueling routine that he had in Minnesota: classes, studying, and working evenings as a janitor and bartender in order to provide us with the basic necessities of life. Even then, he had to rely on both his and my mom’s parents to help make ends meet.

When he was around the house, he was often preoccupied to the point of appearing absentminded. My most consistent memory of my father is of him sitting at the table, head bowed over a book. A true intellectual, he wasn’t the kind of dad who liked to play catch or ride bikes or go hiking, but since we’d never experienced anything different, it didn’t bother us. Instead, his purpose—to us kids, anyway—was to be provider and disciplinarian. If we got out of hand—which we did with startling frequency—my mother would threaten us by saying she was going to inform our dad when he got home. I have no idea why the very notion terrified us so, since my dad was not abusive, but I suppose it’s because we didn’t really know him.

The Notebook

The Notebook Two by Two

Two by Two A Walk to Remember

A Walk to Remember The Guardian

The Guardian Dear John

Dear John The Last Song

The Last Song The Lucky One

The Lucky One The Wedding

The Wedding The Longest Ride

The Longest Ride Safe Haven

Safe Haven The Rescue

The Rescue The Wish

The Wish See Me

See Me Message in a Bottle

Message in a Bottle At First Sight

At First Sight True Believer

True Believer The Return

The Return A Bend in the Road

A Bend in the Road Three Weeks With My Brother

Three Weeks With My Brother Nights in Rodanthe

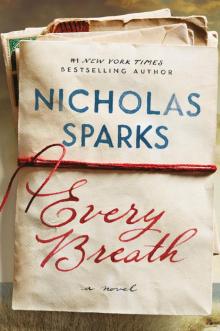

Nights in Rodanthe Every Breath

Every Breath